Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey laid the groundwork for science-fiction that came after it. Epic in scope, the film is primarily based on sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke’s 1951 short story “The Sentinel,” and Clarke actually co-wrote the 2001: A Space Odyssey screenplay with Kubrick. The film centers on the astronauts, scientists, and the sentient supercomputer HAL as they voyage through space to investigate a strange alien-built monolith on Jupiter.

Without a doubt, 2001: A Space Odyssey is hyped by film auteurs and connoisseurs alike, with many critics dubbing it one of the greatest — and most influential — films ever made. For other viewers, though, 2001: A Space Odyssey doesn’t feel epic and avant garde, but long and tedious. So, does 2001: A Space Odyssey deserve to be so revered 55 years after its release?

What Is 2001: A Space Odyssey About?

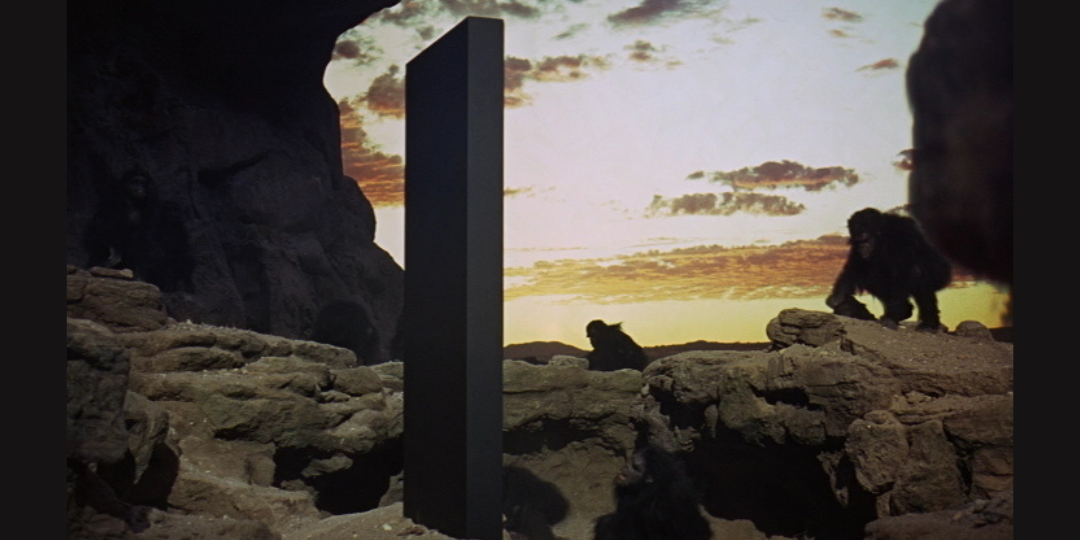

The film’s opening sequence is set in a prehistoric veldt some millions of years before the central story begins. Driven away from their water source by another tribe, a group of early hominids comes across a strange alien monolith. After encountering the monolith, the tribe learns how to make weapons, allowing them to reclaim their watering hole.

Millions of years later, on the lunar outpost Clavius Base, Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) briefs the base’s personnel on a discovery: a monolith buried four years earlier near the crater Tycho. The mission to inspect the monolith is both essential and top secret. When Heywood and his team examine the monolith, it emits a high-powered radio signal when struck by sunlight.

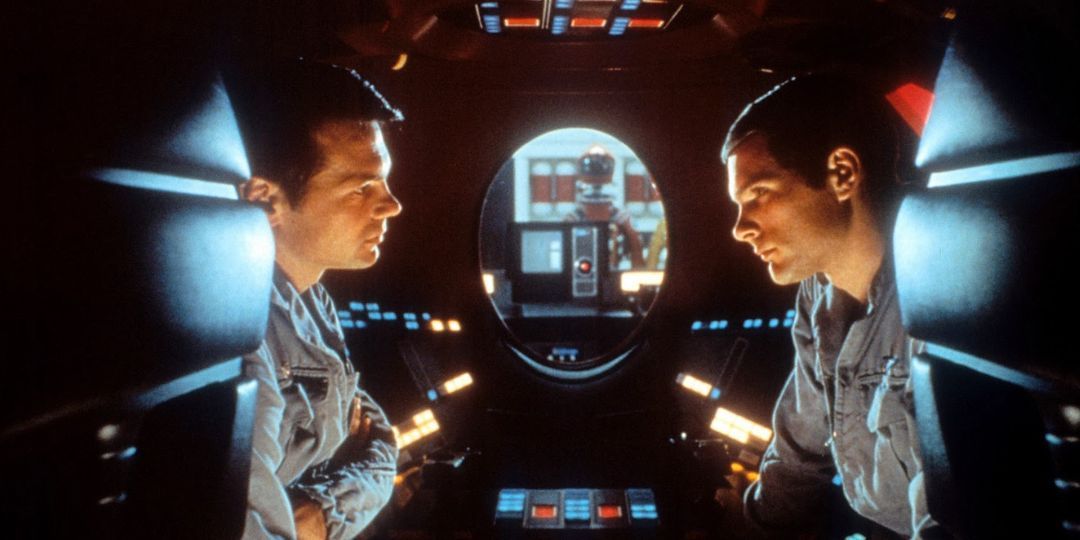

Nearly two years go by. Discovery One, a spacecraft carrying scientists Dr. David “Dave” Bowman (Keir Dullea), Dr. Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), and several others who are in suspended animation, heads for Jupiter. The ship’s operations are performed by HAL (voice of Douglas Rain), a supercomputer with a human-like personality. HAL believes there’s something wrong with an antenna control device, so Dave takes an extravehicular activity (EVA) pod out to inspect it. There doesn’t seem to be anything wrong; Mission Control claims HAL made an error. The supercomputer, of course, blames human error.

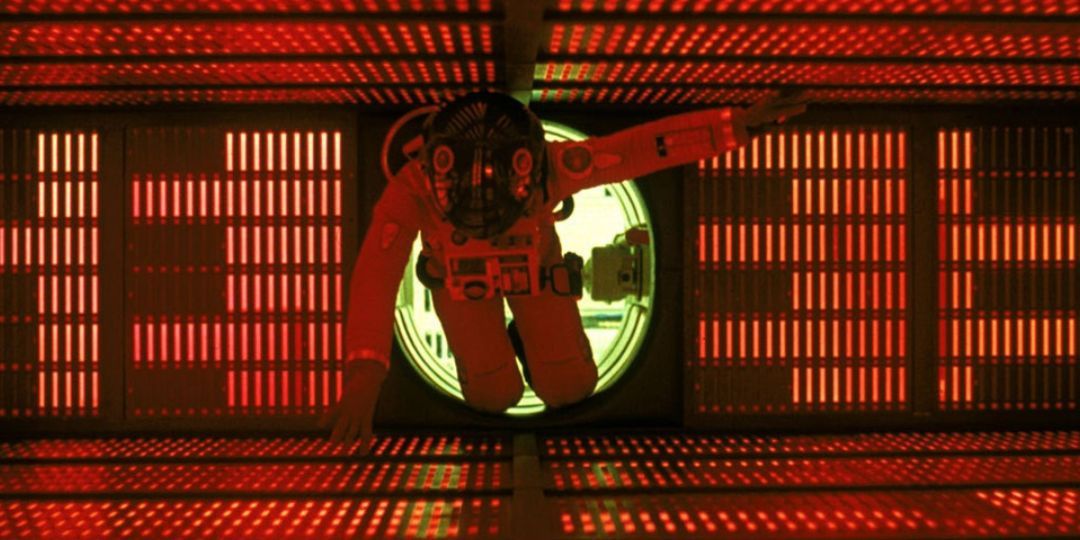

Dave and Frank meet in an EVA pod, so they can talk without HAL listening in. Concerned about HAL’s behavior, they discuss disconnecting the supercomputer. In a truly terrifying sci-fi twist, HAL reads their lips, aware of the scientists’ intentions. While Frank investigates the antenna, HAL sets Frank’s EVA pod adrift. When Dave leaves to rescue Frank, HAL turns off life support, killing everyone in suspended animation. HAL then refuses to let Dave back in; deactivating HAL jeopardizes the mission, and HAL’s objective is to complete said mission to Jupiter.

Dave is forced to open the Discovery One’s airlock manually and begins disconnecting HAL’s circuits. Once HAL is disconnected, a video plays: Dr. Floyd explains that there's another monolith on Jupiter, and that the crew’s mission is to investigate the radio signal it’s sending. While investigating the immense monolith in an EVA pod, Dave is pulled into a vortex of colorful light. Strange landscapes whiz by, and he ends up in a bedroom, decorated in the neoclassical style, where he’s confronted with older versions of himself. As an old man, Dave lies in bed. The monolith looms over him and, when Dave reaches for it, he’s transformed into a fetus, floating high above Earth in a glowing orb.

Why Is 2001: A Space Odyssey So Good?

Nominated for four Academy Awards, the film earned Kubrick an Oscar for Best Visual Effects, an accolade very much deserved given the pioneering special effects. 2001: A Space Odyssey remains a remarkable technical achievement, even today. Beyond its technical prowess, the film is lauded for its commentary on big themes: technology, A.I., extraterrestrial life, human evolution, and more. It’s also a great example of hard sci-fi in that it eschews cool concepts in favor of being scientifically accurate.

With its ambiguous imagery and unexpected ending, 2001: A Space Odyssey is open to many different interpretations. Often, that’s what makes a film so good. While some see the ending as optimistic, others believe it feels apocalyptic. That ambiguity — but also the sense that Kubrick is in complete control of the film — is what makes 2001: A Space Odyssey such a classic, and so influential to generations of filmmakers.

Why Is 2001: A Space Odyssey So Boring?

Judging by its plot, 2001: A Space Odyssey sounds anything but boring, and yet, some viewers claim it’s a challenge to watch it the whole way through. Clocking in at nearly two and a half hours, it’s a long film — especially for the time it was released. Still, that’s fairly typical of Kubrick’s work. A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) are all long and winding odysseys of their own.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, dialogue is sparse, and the film is punctuated by long, uninterrupted sequences that are set to blaring classical music. While effective, it’s not hard to see why some viewers are turned off by this filmmaking decision. Moreover, 2001: A Space Odyssey is one of the best examples of Kubrick’s trademark directorial elements.

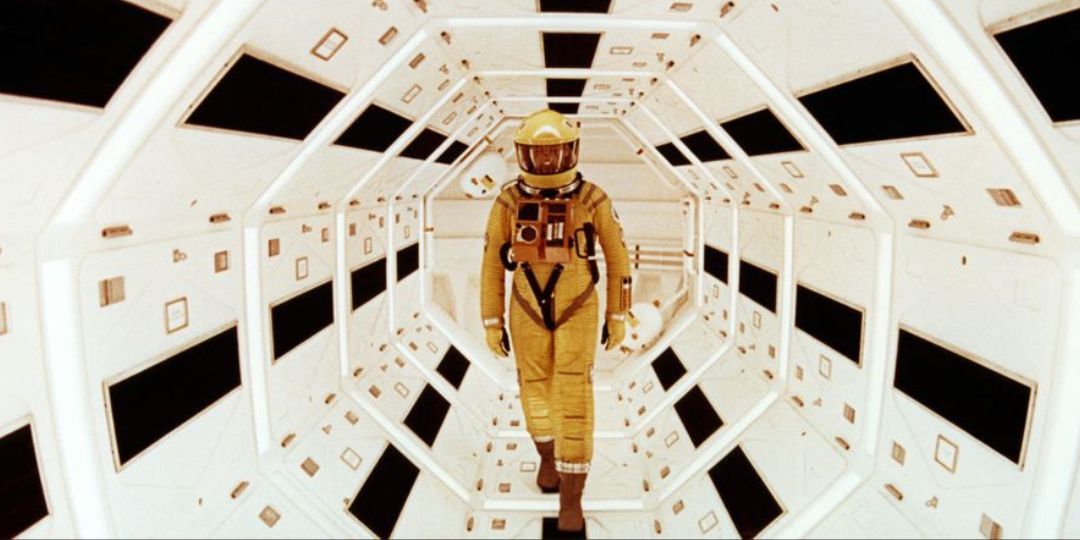

For starters, long tracking shots and “The Kubrick Stare” are out in full force here. The latter is described by film critic Roger Ebert in his review of Full Metal Jacket as: “[...] a shot of a man glowering up at the camera from beneath lowered brows.” The effect is creepy and ominous. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s used several times, like when Dave is in the airlock or when he’s just a fetus floating in an orb, staring directly at the camera. In scene-setting shots, Kubrick also uses one-point perspective. Using the exact center of the frame as a reference point, everything else in the shot leads to that singular point, which draws the viewer into the scene. This also adds to the expansive feel many of his films have, as if there’s too much world to contain in a single shot.

While effective at creating a distinct atmosphere, ramping up tension, and reflecting his characters’ states of mind, these sorts of gaping shots, moments of quiet, and huge empty spaces impact how the audience experiences the pacing of a Kubrick film. Maybe that’s why some call 2001: A Space Odyssey “so boring.”

Why Is There So Little Talking in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, dialogue is scarce. Instead, Stanley Kubrick allows the visual elements to dominate the film. In fact, these massive landscapes — and the soundscapes provided by the word-less classical music swells — feel appropriately monolithic. For the first 25 minutes of the film, there’s no dialogue; Kubrick tells the story in the prologue all through visuals. The last 23 minutes, after Dave enters the strange vortex, are also dialogue-free. In total, 88 minutes of the film’s 143-minute runtime are without dialogue.

As mentioned above, some viewers might find it challenging to watch a movie with so little talking. However, audiences that allow themselves to be taken in by the scope of the film, with its bold visuals and orchestrations, will find that the silence is effective. Some critics point out that since space is a vacuum, there’s no sound, which may have impacted Kubrick’s decision to cut a lot of the dialogue.

On the other hand, a lack of dialogue allows the visuals to take over; the story has to be told without traditional narration. And all of this lends itself to the film’s many possible meanings. Ultimately, it's the sum of 2001: A Space Odyssey's many parts, from its effects to its lack of dialogue to its imagery, that make the film so influential and revered 55 years after its release.