In 11 bit studios' latest survival game, The Alters, worker Jan Dolski is tasked with maintaining and surviving a massive base on a planet, with a sunrise that will kill him, all by himself. His only source of aid is—well, himself. Using a system called The Tree of Life via a supercomputer, Jan is able to create the titular Alters, alternate versions of himself that made different choices and thus have different skills, personalities, histories, and knowledge (via a quantum supercomputer). This means Alters have his body and DNA, yet "recall" different life experiences that didn't actually happen. The result is The Alters, a unique survival game that blends traditional elements of the genre with the twist of Jan's companions, each of which comes with his own story, dialogue, and (possibly) secrets.

Game ZXC sat down with The Alters director Tomasz Kisilewicz to discuss how The Alters differs from other survival games, how it incorporates themes of identity, choice, and regrets, as well as the process of working with a single actor, Alex Jordan, to voice a massive cast of Alters. Kisilewicz also compares and contrasts The Alters with previous 11 bit titles, including Frostpunk and This War of Mine, reveals some inspirations behind the game's distinctive "tire-shaped" base, and touches on the difficulty of writing branching dialogue and narratives for so many similar yet different characters. This transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

The Alters Blends Social and Survival Elements

Q: You mentioned the philosophy of regret, and regretting choices. Could you explain how you went through that question in the game?

Kisilewicz: We were looking for a nice space in which we could explore this topic, sort of just test it out. How can we create people like The Alters? That obviously moved us to the sci-fi genre because it is an abstract idea. It's very close to a question we asked ourselves, which is not so abstract, but there was the execution of it, really seeing the outcome—it has to be abstract. We felt like, if the person was really supposed to do it, it was very important to us that this is a story about a person who does this thing, and it happens to him.

It's not like he accidentally steps into an Alter or something. At this stage, we didn't call them Alters yet, of course, but we wanted him to have full agency over it, as the player has full agency. We felt that, okay, he needs to face some harsh circumstances. I'm not sure how and when exactly we ended up on this planet, but it was like, "We want to make this sci-fi game about this sci-fi topic." I think, many times, with sci-fi works, we need to create the circumstances that allow us to venture into those philosophical questions. The distant planet where he's alone, and he's facing problems he can't face on his own, that's forcing him to make something unspeakable and then learn something about himself in the process.

Q: And you do so very uniquely, with the genre meshing. You've got social sim, base management, resource management—how did you decide what to include?

Kisilewicz: It's survival at its core with the base building. At the same time, there's a very strong narrative-driven approach to dialogue. There's a lot of dialogue, because these Alters, from the beginning, we wanted to really ask them questions. What's most interesting now is not reading about how my life turned out, but how it could've turned out. It's going to the bar with this guy and being like, "Hey, you know, after a year, tell me, what was it like, because I always wanted to do this thing, but I never had the courage. Apparently you did, so tell me about this experience."

We wanted to create this kind of situation, where they can just hang out and discuss it. Of course, it requires you as a player to invest some stuff into the relationship with the Alter before he opens up. It takes some time, but then he opens up, and you learn something amazing about him and, in the process, about yourself. The relationship is beneficial to both of them—they can evolve and learn from each other.

For all of this to happen, you need this tension. The survival genre, which we feel very confident in with our experience from This War of Mine and Frostpunk, is pushing us to do these things. I always like to describe it like this: "Okay, well, I have to figure out a new technology, so it would be great to have a version of me that's capable of conducting research. That's great. I can create a scientist version of me that didn't drop out of college, and that had a great career. It seems so great."

You create this Alter, but it turns out, he's a very smart and also a very ambitious person. He soon starts to sort of undermine your ruling as a leader. "So I actually created more problems," you say. "I solved some problems, but I added more. Now maybe I should create a guard Alter, or maybe I should create someone who will calm them down." That's up to the players. That's agency.

Each Alter Has A Story To Tell

I liked bonding over the dad with the first Alter. I had made the scientist, and said, "Maybe you should go ahead and just rest," and he's like, "No, no." I also liked the miner I've seen before, the one with the phantom pain when he gets an arm back. That's such a cool concept.

Kisilewicz: The special thing about this game, I think, differentiating The Alters from multiverse stories is that they are not taken from some different universe and there's a home they can get back to. They feel completely real, but their minds are just a recalculation of our minds based on the variables of different skill sets. Things feel perfectly real to them, but they're really not. The phantom pain—the guy who lost his arm, he feels this pain, but it's not there. What do we do about it? And, you know, sometimes it can be very pessimistic at first.

In other cases, there can be some hope for it because, maybe, he's lost someone, and that made him who he is. Maybe now, in this world, maybe this person exists. Maybe he can find this person. There are a lot of themes of "lost and found," both to people, to items, and to memories. Each Alter has his own storyline that has these kinds of story pieces.

Q: How do you tie the individual stories of these characters, who are very similar but different, into the overarching narrative?

Kisilewicz: In a very tricky way. The charts for our storylines are the worst kind of spaghetti. There's a main storyline, which is branching, but then you have the Alters' storylines, which also have their own course that you decide on. You also decide what Alters you have and we, as creators, don't know what Alters you will have at which stage, so we had to prepare the main story in a way that serves this kind of structure and is seamless underneath. That's not the worst part.

The worst part is, underneath, we really wanted to have this emergent narrative that comes directly from the systems. As you can see, when you talk to the Alter, each decision, each dialogue choice in a little way affects his emotions. When he's angry, some events may occur that will affect everything else, and you really have to juggle all of this. Which is tricky as a player, but even trickier to create. It's a lot of testing and iterating and feeling like some stuff doesn't work, so we have to restructure it. Right now, we're at the stage where we feel confident with the structure we have. It was a ride, but we're getting there.

Q: So, depending on player choices and who they make, is it possible to get all the Alters by the end of the game?

Kisilewicz: No, it's not. It's not possible to have all possible alters in one playthrough, that would require another playthrough, But thanks to the structure I just mentioned before, it's nice to play the game again. Maybe make some different choices in the main storyline. Maybe make different Alters, maybe treat them a different way, maybe have a different economic strategy to the game. There is definitely this replayability.

We also wanted the choices to really matter. It's great that you can't have everyone, because you have to figure out: which one do I really need? What do you want to have in the Tree of Life? You think, "Maybe I need a miner because I need to mine fast, but maybe I'm more curious about that botanist guy. I'm curious about his personality, so that's what I'm going to create. And that will change my strategy and the economy of the game."

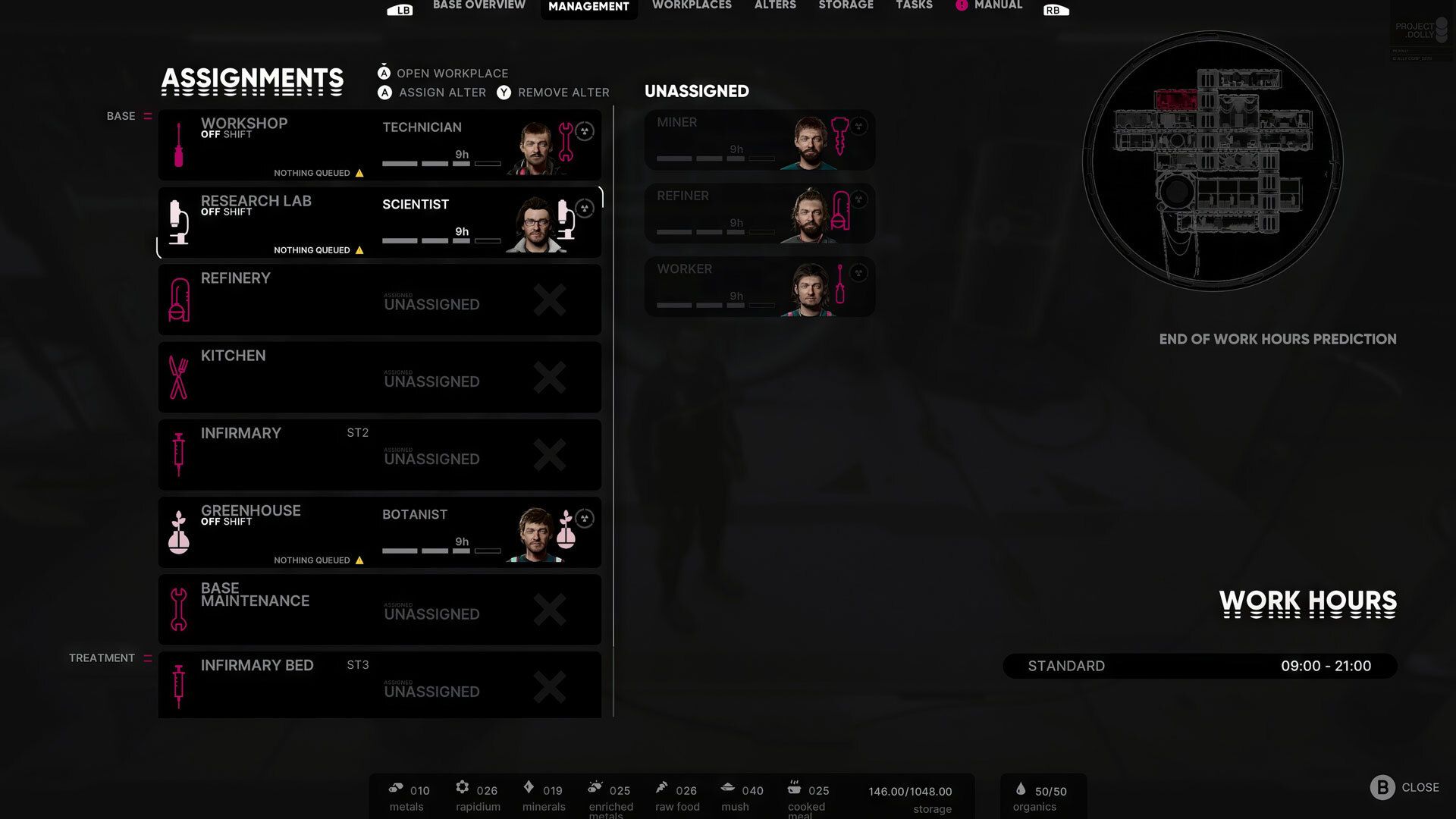

Building And Managing A Modular Base in The Alters

Q: One thing that really caught my attention while playing was that, when you do your tasks, time speeds up. Obviously, time management is very common in the survival game genre,. but I definitely wasted a few days early on when I was trying to figure it out. With time playing such a big factor in the game, how rewarding or punishing do you think that system is designed to be for players?

Kisilewicz: It's subject to a lot of balancing work on our side, and we're not finished with this yet. We're still working on it. We're conducting a lot of playtests with the players to see how much time they need for certain tasks, if we should make the tasks easier, or maybe give more time to see what works best. We don't want this game to be hardcore survival game. It's not going to be a survival game in which you constantly die and try to make things better. However, there is this loop of replaying certain parts of the game, not only because you die, and you want to go back in time a few days, but maybe because you feel, "I could approach this in a better way." It's not a problem for you to go back.

We were actually testing different approaches to a save system, and we changed how much freedom we give players to go back. We finally decided to save the game at the beginning of each day, like This War of Mine, but with the possibility of going to the particular day that we find suits us best. It's similar to the first Frostpunk, as well. When you're logged into the game, into your own save, you can see the status of the base, the status of the Alters, and find the point where things were okay. And if you effed up something later, you could go back there.

Time is really the most precious resource. We were worried because it was important that you be that person doing the task. When you assign tasks that take time to other people, we never wanted to have a "speed up time and wait for the outcome of this work." We decided to speed up time when Jan is working, which results in this seamless playing where you don't have to wait for anything to happen.

Q: How did you settle on the ship design? I like it, it reminds me of a tire.

Kisilewicz: There's this movie, Murderous Tire, or something like that. I wouldn't say that was an inspiration, but maybe subconsciously. The truth is, we really wanted to do something one-of-a-kind. The easy answer would just be, "We like circles," because in Frostpunk your base was in a circle, but that's also not the truth.

The movie reference is likely Rubber .

The truth is, we were looking for some iconic shapes, and it was supposed to be a mobile base. We were testing different things, like some train-like structures, but this concept just felt good when we saw it. It sort of makes sense with the modules, because modularity is so important. It had to be mobile. It had to be customizable. With the circle—with the "tire"—we have this closed structure, which is great.

Q: To that point, how modular is the base?

Kisilewicz: It became apparent after some time that we didn't have enough space within the circle, so we're actually enlarging the circle, the whole tire, to fit more modules inside. We have storage modules. While our economy grows, we need to have more space to store all the resources we gather from the planet. Having new Alters, having new topics, brings new ideas for the modules. The modules you saw on the list earlier, that's not all the modules we have.

There are some modules you can research at any given time, while some are uncovered during the story or the storylines of the Alters. There are a few, I think, four tiers of the base, that you are expanding throughout the whole game. By the end, it's like a pretty big wheel. It's not like hundreds of modules, but it's substantially bigger than at the beginning.

One Actor Plays Jan and All His Alters

Q: What were the challenges of working with a singular actor who plays every role in the game?

Kisilewicz: Alex Jordan is so passionate. He's a great actor, and that's the most important thing. The casting process was very long because we had to make sure the person could pull off all the voices. We had amazing actors in the process. They were all acting very well and had interesting takes. But with Alex, we really felt from the beginning, "That's a match." That's really Jan. The Jan that I was writing, I could hear him speaking. The passion that Alex brings to the project is a lifesaver in moments where you have tens of sessions and hundreds of hours of recording for just one person. And Alex, no matter how long it takes, how many sessions—we sometimes can be exhausted, but he never is.

Q: I believe he said his time in the recording booth totaled up to about a month for the entire project.

Kisilewicz: And we're still not done! It's not only dialogue, but it's all the bar conversations and dialogue that will happen later. You'll see more of it in the days later in the game. His talent and his craft are so amazing. He can really be in those characters. It's so difficult. They all need to have the baseline of being Jan Dolski because they all have the same core, but they also need to be different, distinguishable. But we don't want them cartoonish, right? That would be too far. You have to find this perfect balance. It was a process. Finding it was one thing. Maintaining it for hundreds of hours of recording, that's a second thing.