Studio Ghibli has long been recognized as a powerhouse in both anime and general film history. The studio has consistently put out enchanting, unique tales that touch on everything from the power of childhood imagination to the history of an aeronautics engineer. While many of their films hold places in the hearts of many, Spirited Away has been regarded as one of their best. Looking back 20 years later, what is it about this strange, intriguing story that has made it stand the test of time?

Releasing in Japan in 2001, Spirited Away found immediate success and quickly outpaced even Princess Mononoke. The North American distribution rights were soon purchased by Disney and the English dub of the film was released in 2002. The film would go on to gross nearly $400 million dollars worldwide and held the record for highest-grossing film in Japan for 19 years until it was surpassed by Demon Slayer: Mugen Train. It went on to win multiple awards and be voted into lists for the best film, animated or not, of all time.

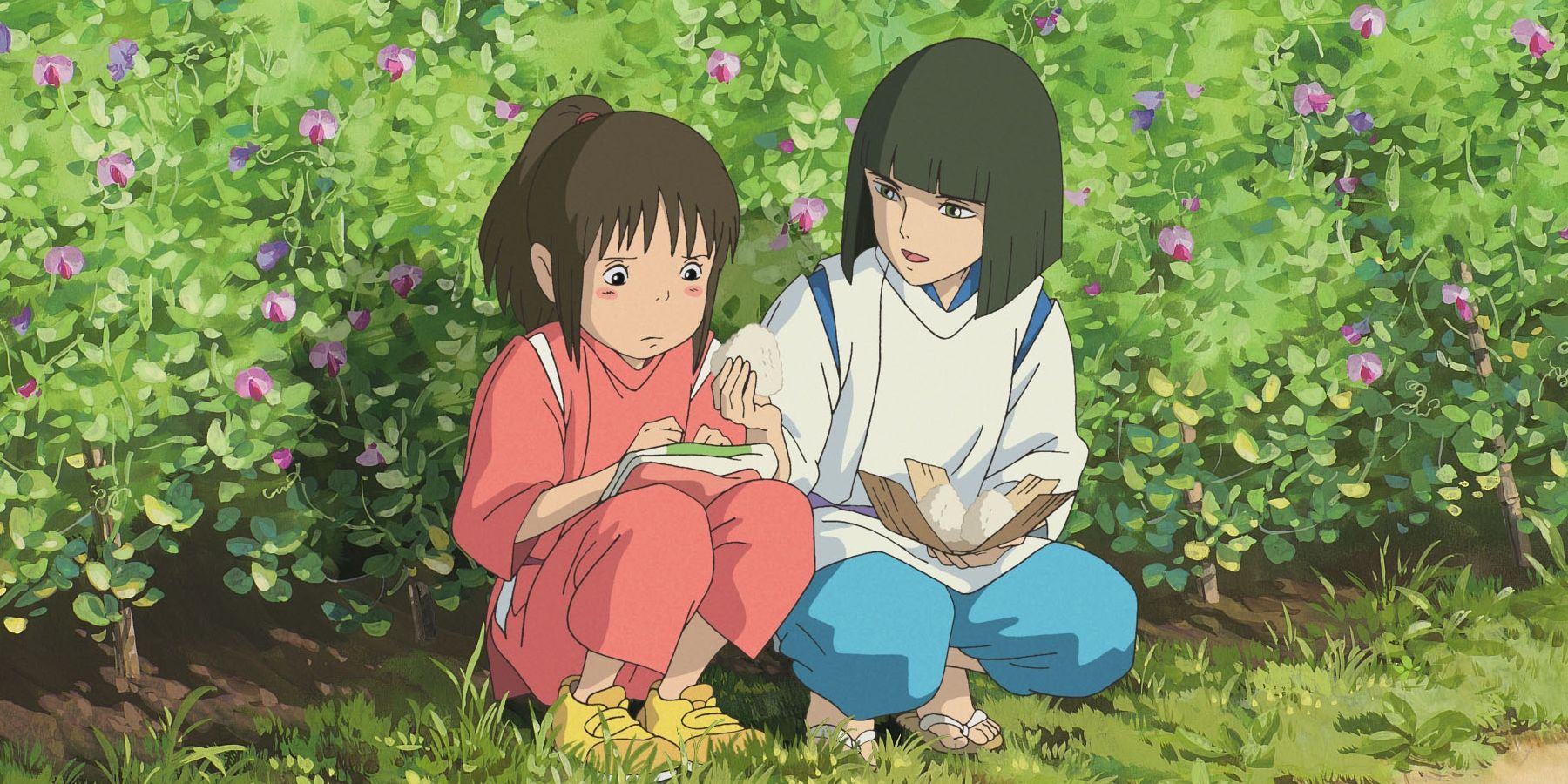

The story itself tells the tale of Chihiro, a young girl who gets trapped in the spirit realm following her parents being turned into pigs. While this story seems somewhat strange on the surface, the way it plays out is beautiful. From the art direction to the character design, Spirited Away showcases Studio Ghibli at some of its best work.

While many have questioned what the story overall is in reference to, as this is a common notion with Ghibli films, this isn’t ultimately surprising considering it touches on many themes. First off, there are the obvious themes of supernaturalism stemming from the spiritual world Chihiro finds herself in. There are also themes of fantasy, as this film has often been compared to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Despite these themes being ever-present in the film, there are other themes that become clearer upon further dissection. One of these points toward a critical commentary on Japanese generational conflicts. At the time of the film’s initial release, Japan was facing an economic downturn and much of their society was turning back to the old ways of their society. Chihiro is meant to emulate this turn back, as she seeks out who she was before entering the spirit world.

Another prominent theme is criticism of foreign consumerism of Japanese products. Chihiro’s parents being turned into pigs upon consuming an excess of food is a fairly on-the-nose metaphor. They become literal capitalist pigs, endlessly consuming that which is not theirs with the promise that they “have enough cards and cash” to pay for it afterward. Hayao Miyazaki, the writer and director, has commented on this, stating that many became these pigs during Japan’s commerce bubble in the 1980s and have never stopped consuming.

This consumerism theme permeates even further. The bathhouse, while a traditionally Japanese locale, is led by the witch Yubaba who wears a more traditionally European dress and is surrounded by European furniture. Her employees however live in more minimalistic Japanese-styled housing and wear more Japanese-styled clothing.

No-Face stands as a way to highlight the excess and greed present within the bathhouse. He consumes all and trades gold for the labor. While the workers will do anything it takes for a chance at this excessive gold, it ultimately amounts to nothing. The gold is false, and thus everyone was buying into nothing. All of their labor has been devalued, representative of an economic bubble bursting.

One of the other prominent themes is that of nature and humanity’s pollution of it. The most direct reference to this is with the sludge monster that makes its way into the bathhouse. The workers all try to turn it away, alluding to the general population wanting to ignore and wave away the pollution of the environment. While being cleaned, Chihiro and the rest of the staff pull a plug out of the side of the monster that is revealed to be a bike. After the bike comes a seemingly endless pile of trash, boxes, and more; all things that are unfortunately commonly dumped. Upon this pollution being released, the river spirit is freed.

Another allusion to this comes with Haku. For the length of the film, he can’t remember who is and is also in search of his past. Chihiro is able to free him by remembering that he is actually the Kohaku River, which she then points out has had apartments built over it. The human need for development, construction, and expansion led to nature being destroyed and this river spirit being lost.

Even 20 years later, Spirited Away houses themes that are timeless and sadly still very poignant in the modern age. Consumerism, environmentalism, and spiritualism are three elements that Miyazaki very much cared about. His passion for these themes and his artful method of sharing them are the central reasons why this gorgeous piece of art still holds up today, and why this film will forever stand as among the medium’s best.