Some movies take a long time to make and when they finally come out, it can either feel like the long development took its toll or like the wait was completely worth it. When Takeshi Koike’s Redline came out after seven years, it was most certainly worth the wait and has rightfully been considered one of the best-animated films ever made, but that should not be where the story ends.

Takeshi Koike has been in the business since the late 80s, working his way up the ladder and having found room to grow at Studio Madhouse, working alongside the likes of Yoshiaki Kawajiri. As his skill developed, his unique style of animation and even more unique character designs became a trademark that fans could recognize almost anywhere.

Who Is This Guy?!

In a 2013 presentation titled “Sakuga: The Animation of Anime,” presenter Colin Groesbeck called Koike one of the best animators ever but expressed that his early work wasn’t super special. He shared his opinion that many talented animators tend to be undiscovered for quite a while until they’ve been given the chance to prove themselves, and Koike got such a chance in the early 2000s.

In 2000, he animated the opening to the otherwise live-action film Party 7, an absolutely wild short packed with chases, fights, dancing, and more. The detailed slow-motion and thick black shading evoked the aesthetic of western comic books but moved as effortlessly as the best of Japan’s animated features.

His talents didn’t go unnoticed by the Wachowskis, who scouted him to direct one of the Animatrix’s most gorgeous shorts, “World Record.” It’s hard to look at such breathtaking slow-motion animated on 1’s without seeing the insane amount of time that went into it. And Koike’s signature style would be a big draw for projects like Afro Samurai and Samurai Champloo.

The way Koike animates is excellent, but when he’s given the reigns to design the characters in his own style, the look of the project can be transformed eternally. Shading aside, Koike’s character proportions are often long and tall. They can be cartoonishly bendy or posed dramatically, but no matter what, they are dripping with character in their expressions, marking them as considerably more lively.

Koike’s presence is a blessing and can even elevate some projects to the point that his contributions are remembered more than the whole of the art itself. Afro Samurai is remembered fondly, but it’s hard for the TV series to top Koike’s pilot for the project (just like with the Iron Man anime pilot). It was inevitable that Koike would eventually get to helm his own major work, though it would take some time before fans would get it.

The Seven-Year Sensation

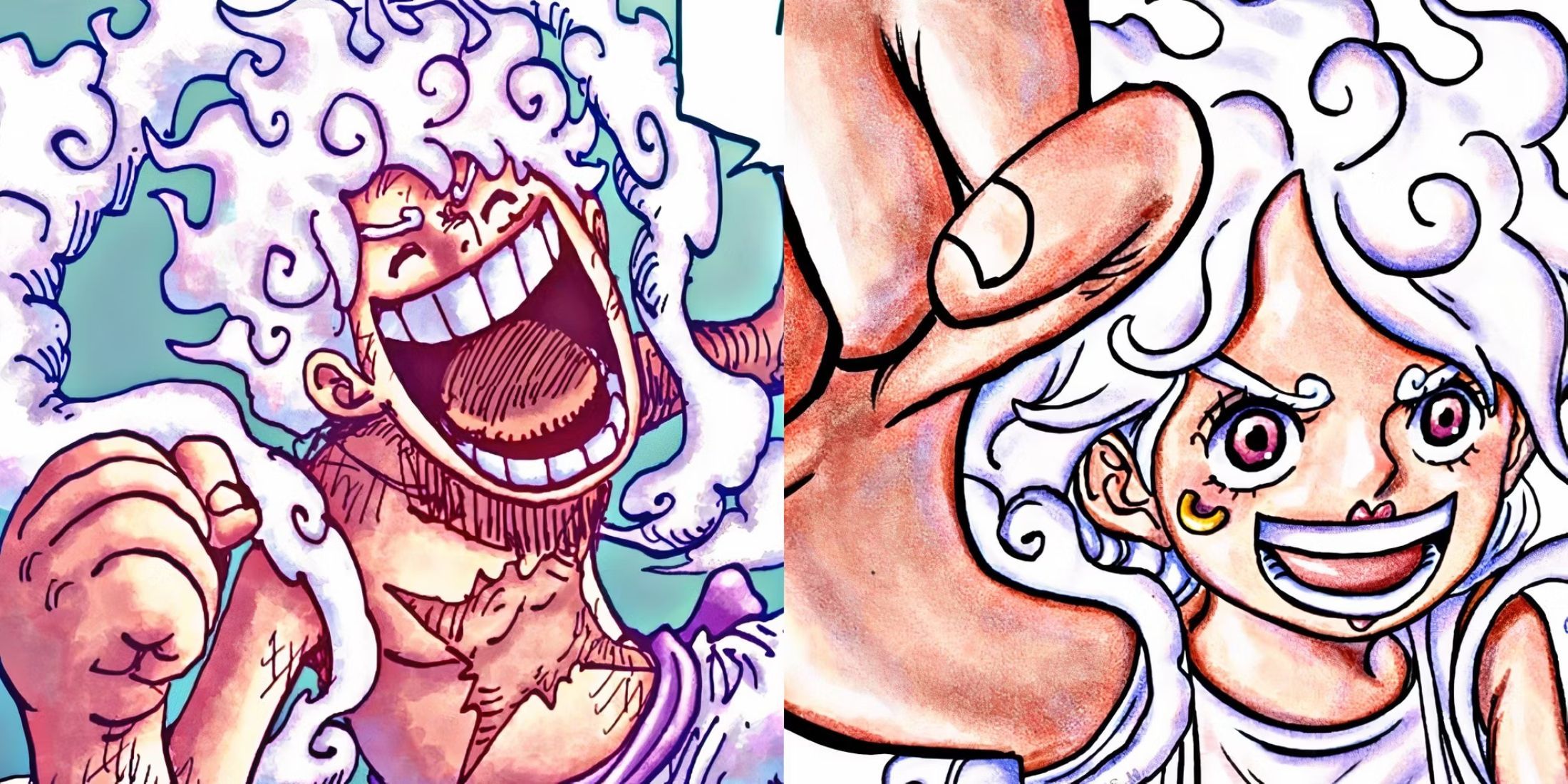

Redline famously took seven years to complete, and few who have seen it would argue that it wasn’t worth it. Few projects can make the product at the end of such a long development feel worth it. More often than not, the long wait raises red flags. It would be foolish to assume Redline’s production suffered no roadblocks but the final product… certainly speaks for itself.

The first two years were pre-production, in which the creative minds behind it went above and beyond, from world-building to mechanical design, alien species, and lore. Koike and Madhouse wanted to ensure that the film was not only complete but that the larger world surrounding the story’s beating heart was just as pristine. It felt bigger than its simple premise, rewarding the viewer upon rewatch with new things to get lost in.

In fact, it says a lot that this film’s most recurring complaint is that it ends, and in fairness, it does end quite quickly - maybe too quickly. But that haste feels awfully fitting, in that it goes out at the peak of its adrenaline rush, and barely any loose end left unresolved or at the very least, unaddressed. A guy, a girl, their dreams, and their combined goal, past a finish line.

When people despair at it being over too soon, it’s funny to remember that the film actually went 30 minutes over the originally planned 70-minute runtime. Redline’s problem was its ambition, which demanded great feats from its artists, contended with less-than-stellar returns, though it’s difficult to get an exact estimate of its budget.

A moot point perhaps; it underperformed. Yet, it gained a following through the home-video release. Failure or not, it would feel inappropriate to call Redlineover-ambitious, as it most surely achieved something over that long production cycle that fulfilled its core promise. It simply took audiences time to realize it, as unfortunately is common with underappreciated art.

Redline is relentless, constantly moving, and refuses to be constrained by the limits that even the best-animated films before and since have often been compelled to yield to. The film took a bullet for this ambition, but it’s regarded by many as one of the best works of animation ever made. So what does a director like Koike do after that?

He Never Really Left

When Koike comes up in conversation, Redline is on the tip of everyone’s tongues, followed swiftly by the works that built up to that point. After such a huge cult classic - one burned into the community’s consciousness - it can be easy to lose track of the man in the ever-shifting tides of the community. But even if he hasn’t made anything quite as far-reaching as Redline, he has most certainly not disappeared.

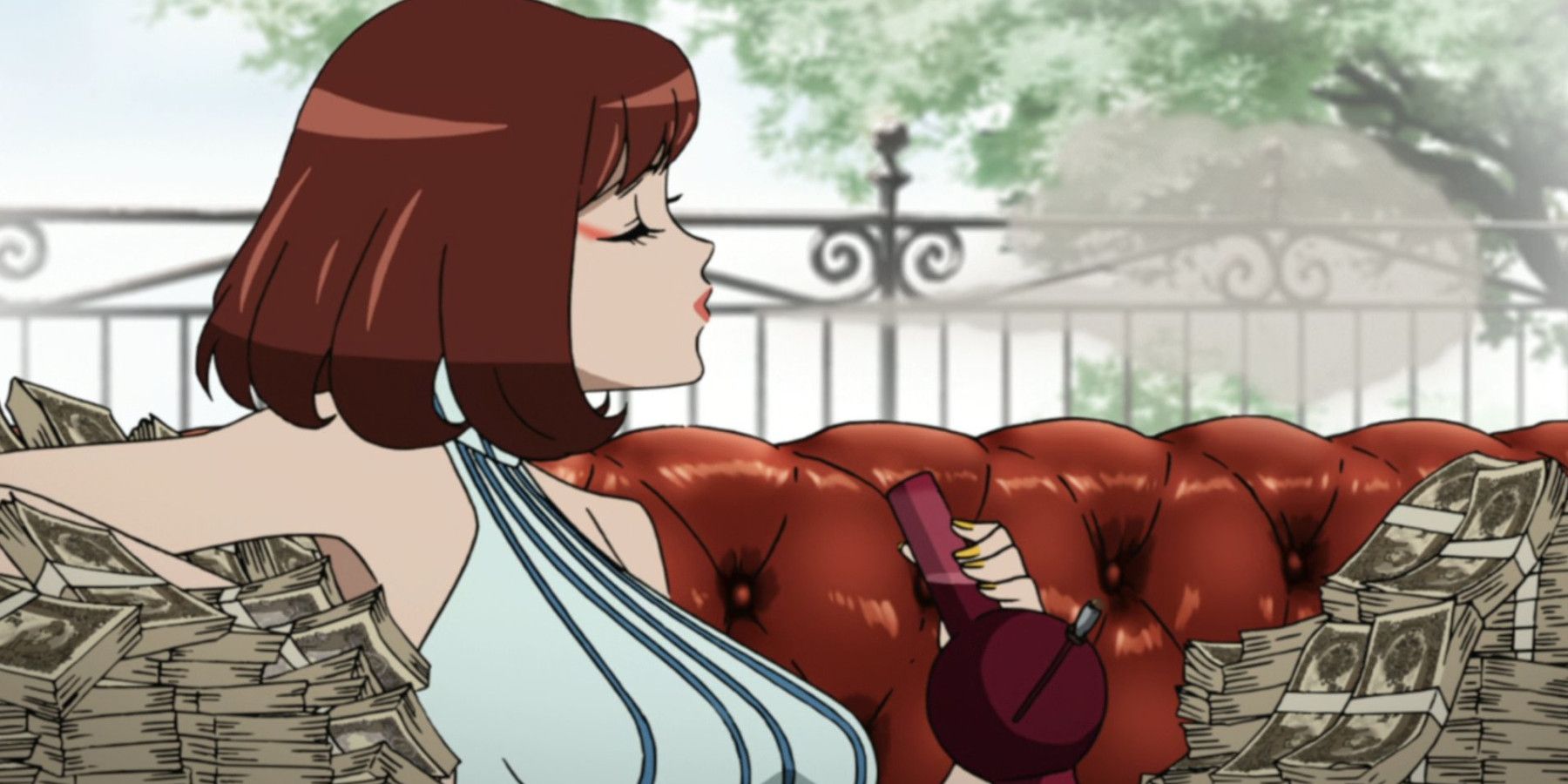

In fact, fans of Lupin the Third know very well where Koike has been, ever since Sayo Yamamoto brought him on boardThe Woman Called Fujiko Mine, one of Lupin’s most acclaimed modern hits. Yamamoto’s vision of Lupin was bold, more mature, and a fresh stylistic take on the classic series, but Koike’s contributions can’t be understated.

He was brought on as a character designer and even directed the first and last episodes, but this was just the beginning of his time with Lupin. Because two years later, Koike would direct once more, with a new series of short films, each one focused on one of the main characters, starting with Lupin the IIIrd: Jigen’s Gravestone.

These films are direct continuations from Yamamoto’s series and thus are on the more raw and mature side of the Lupin the Third spectrum. They’re bloodier and aren’t afraid to put the characters through some punishment. His second Lupin film, Goemon’s Blood Spray, feels like Koike’s return to the raw stylized body horror of Afro Samurai.

Goemon’s Blood Spray, in particular, is one of the most widely shared Lupin stories of recent years, be it AMVs or tributes. Some of the most iconic moments of modern Lupin are found within it. The last film to come out was Fujiko’s Lie in 2019, but fans are hopeful for a continuation, as Koike has been building a connected story between the films.

Takeshi Koike hasn’t gone anywhere, and it’s safe to say that if he’s working on anything, it’ll be worth the wait. Just as was the case in his early career, his work as a key animator, or even his character design work on shows like Yasuke, might not be him at his best. Only as a director is his full power revealed, and as shown with Redline, good things come to those who wait.

.jpg)