Time flies when you’re having fun - at least, that’s how Rebellion founder Jason Kingsley looks at his 30 years at the helm of the Oxford, UK games studio. “I think it's only at times like Christmas where you have a bit of spare time on your hands to look back and say, ‘Yeah, that was a really good game, wasn't it? Oh, that was really cool.’”

In the three decades that Rebellion has been involved in the industry, it has grown from a skeleton-crew outfit developing games for big publishers into a multinational corporation responsible for major franchises like the Sniper Elite series, and also an arsenal of publishing and intellectual property ventures. Game ZXC spoke with Kingsley to look back at Rebellion’s last 30 years and to talk about his vision for the studio’s future. Interview edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: First off, congratulations on 30 years. That’s a long time to be making games. How does it feel to have come this far?

A: Well, I believe that if you murdered somebody in England, you only get 20 years in prison. So, you know, we’ve been in for time-and-a-half of a murderer’s sentence.

It actually doesn't seem like it’s been very long. The reason for that is that I, Chris [Kingsley, brother and co-founder] and everybody at Rebellion are always excited and worried about the next project we're working on. So, you look back at projects we've done that have come out successful, and you've already moved on to the next creative thing you're doing. I think it's only at times like Christmas where you have a bit of spare time on your hands to look back and say, ‘yeah, that was a really good game, wasn't it? Oh, that was really cool.’

We've done quite a lot, actually. But when you're in it day to day, building the next game, or working on the next piece of technology, the next brand, whatever it is, you're sort of in the moment creating that. What's happened in the past and what's going to happen in the future are sort of separate from doing what you need to do now.

So, it's humbling to think we've come this far. It's also a little scary to think that 30 years have gone by. We never set out to be around for a long time, we just set out to make good games. I guess you could argue that's the best thing to focus on.

Q: Let’s talk about the history of Rebellion a bit. Could you give me an abridged version of how the studio got where it is today?

A: Crikey. Well, we were set up in 1992 by Chris and myself. After we got our first employee - we didn’t really even know how to do that - we worked with Atari on Aliens vs. Predator and Checkered Flagon the Atari Jaguar, which was a really interesting system to work on. We then got spotted by 20th Century Fox when they were kicking off their games development division. They asked us to do another version of Aliens vs Predator on the PC, which I suppose is one of the games that put us on the map as a company.

People realized that we could do tech as well as games design. We've always innovated in our games. We were the first company to do the equivalent of photogrammetry; it wasn't even called that in the original Alien vs. Predator. We built models for that game and photographed them. We were also one of the first companies to do Gouraud shading back in the day in Eye of The Storm. We've had a better track record of innovating in technology, and gameplay as well, as we've gone on.

We also did a lot of work for hire for many, many people. We worked on James Bond games and Simpsons games, and goodness knows what, there are tons of things we did, they’re all blurred together. In the year 2000, we acquired comics, the comic 2000 AD, which was home to Judge Dredd. We started to expand our ambitions into intellectual property and other areas of business.

Around the same time, we decided it was quite important to us to start developing and funding our own games directly. And that coincided with a rise in the digital space that would allow us to sell games globally. Steam was just beginning to come online.

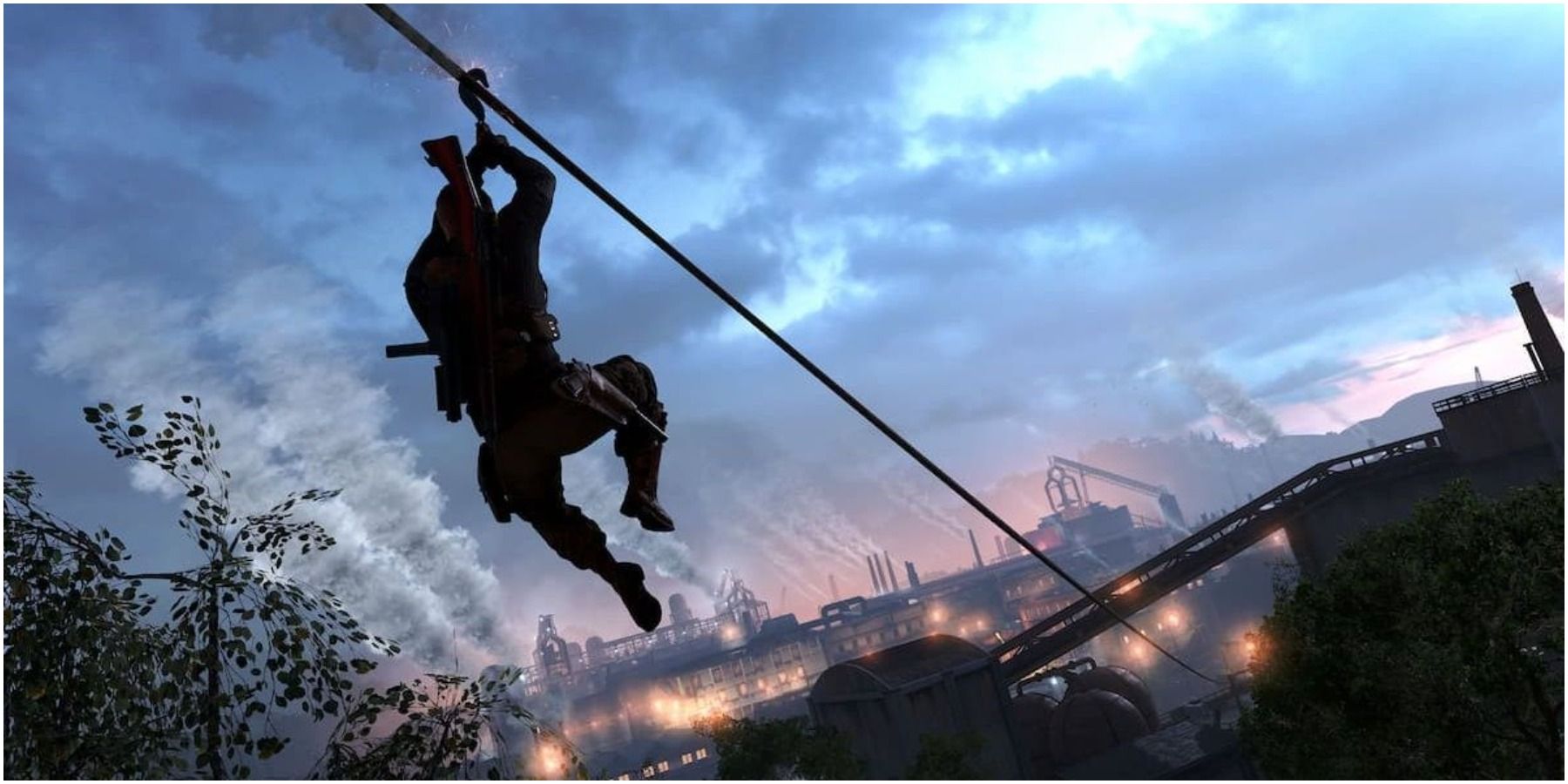

Before Steam, if you wanted to publish on consoles, you weren't allowed to unless you were a publisher. It was a bit of a closed shop. As the years progressed, though, both Sony and Microsoft, and even Nintendo for that matter, realized that the distinction between publishers and developers was really blurring quite a lot. So, we started to self-publish, and one of our major successes of self-publishing has been the Sniper Elite series. We’re on Sniper Elite 5 now, and we sell our games everywhere in the world, physically and digitally - but ever more so digitally these days.

Q: Rebellion’s been around longer than me, which is wild to think about. You’ve probably watched games technology change drastically in that time.

A: Things like the Internet, which came in around the same time that we set the company up. At that time, the Internet was really a very specialist, rare thing. The idea of Googling something, or Facebook, or Twitter, those things didn't exist. The idea of tech billionaires was a sort of odd thing. The landscape has completely changed since then. Digital distribution was a bit part of that, easy access to people around the world if they're connected on the Internet. That’s absolutely amazing.

Q: I think the shift from physical to digital distribution is such an interesting example of how intertwined Rebellion has been with the history of the games industry. What sort of other technologies did the studio witness?

A: Changing formats was another one. We were there the first time, the phrase ‘next-gen’ was used to talk about consoles. We were there at the beginning of PlayStation, we were talking about next-gen games with Sony before most other people. At the time, what we meant by next-gen was the PlayStation 2. When PlayStation 3 and the Xbox 360 came along, we were talking about a new next generation. We started to joke that we shouldn't call it next-gen, because we were already talking like that for the last format.

Media changed as well. A lot of games were delivered on cartridge, you know, on a chip. They were expensive to manufacture. If you ordered wrong number of cartridges, you got left with a landfill of the things. I can remember delivering games on floppy disk. I remember putting floppy disks in the post because it was the quickest way of getting data from me to a colleague that was working remotely. Sometimes, the quickest way was to get in the car and drive it to them.

I remember using dial-up modems, and building the first pre-Internet games where you could almost type as fast as the data was transferred. A lot has changed. We weren't right at the very beginning of the games industry, that was the generation before us. But, we were really close to the beginning of it. And it's amazing how history repeats itself.

Q: All this must have given you an immense sense of perspective about the industry, and how far it’s come.

A: Yeah, it does. But, it’s also sad because over our history we’ve seen some repeat bad actors in the industry. These are people who are not as ethical as you might hope they would be. You see them come and go in the industry. You try to warn some younger developers about it, saying ‘guys, don't do this, this is a bad way of working, you will get screwed over. Don't do it.’ But they ignore you, and get screwed over anyway.

But, that is the way of history: the ancient Greeks talked about how the youngsters were ignoring them. So you know, that's not new for us. You just have to make your own mistakes in life sometimes.

Q: Can you expand on that a little? What sort of mistakes have you seen younger studios make that you’ve tried to advise against?

A: One of the biggest challenges for an indie is discovery. How do you get people to even know your game exists, let alone play it? How do you get discovered? How do you rise above the noise? How do you use social media to navigate communication? These days, it's all available to you if you're a bit clever, and if you're willing to work hard, and smart, and do a bit of a lot.

Back in the day we didn’t have anything like social media. You had to deal with magazines working on deadline, and websites were not that important. It was a very different space back in the day.

Information flow has been democratized nowadays. There are fewer gatekeepers, like magazines. There are still some gatekeepers, people who are really important to communicate with, but they're not the only way of communicating now. Whereas once they were literally the only way of doing it.

Another thing is indie devs underestimating how long it might take to make a game, especially in the end process. The polishing process at the end of game design is one thing, but you've also got to make it work. You've got to make it not exactly foolproof, but it’s got to be robust enough for it to work.

One of the issues I have is with the green-light or early access process, the idea of people getting to see a game before it's finished. How do you keep the energy up to actually get the game finished properly? You’ve already launched your game, in a way. You've had the exciting moment where your game idea is suddenly being played by other people. That's great, but now you've got to plug along and finish it.

The problem with that is often that it's hard to keep going, it's hard to stay motivated. And sometimes, people can expect the moon on a stick with a game that isn't finished. They expect something big, and then you disappoint them. We've probably all gotten involved in projects where we were terribly excited to support it and follow along in development, but when the thing gets finished, you get it, and you’re kind of like, ‘ah, okay, it wasn't quite as exciting as I thought it was at the time.’

That's okay, these things happen, you can get excited about wanting to support something creative. That’s a great process in itself. But sometimes, when the things actually finished, it can be underwhelming, and that proves a bit of a problem sometimes when managing people's expectations.

Nobody makes a game wanting it to be anything other than brilliant. But not all games can be brilliant. Sometimes, it's just impossible to get the game as perfect as you would like it to be. But it's still a good game. Managing people's expectations about that is an important thing, I think.

We know there are big games out there that have got caught up in this trap. No Man's Sky, for example. That was a really interesting and clever game but its release underwhelmed people, because they promised more than they delivered. That's always dangerous. As somebody who talks to people and communicates outwards, it's always tempting to get terribly excited about your own ideas and to throw them out there. But, if you promise the moon and you don't deliver it, people are going to get disappointed.

If you merely promise a great game, and it is a great game, then everybody's going to be happy.

Q: I think that’s an interesting point. I talk to a lot of indie devs who say that early access and greenlighting has been a transformative part of their development workflow. It’s fascinating to hear you voice the opposite side of that - that those avenues might set unrealistic expectations for one’s audience.

A: It's a different way of looking at it, obviously. For some people, the idea of crowdfunding and early access is an essential part of their business. They need it, because they've got to fund the thing. We're in a fortunate position where we are profitable.

I still claim the right to call us indie, because we genuinely are independent. Chris and I own the company. We're games makers. Yes, we've got over 500 members of staff, but we still make our own games 100% our own, so we definitely ought to be indie. But I also know that indie tends to mean smaller scale. Perhaps we need to come up with a different term, maybe ‘super-indie.’

Back to greenlighting, I’ve always felt that your green-light moment is your launch. But using greenlighting or early access might be essential to a studio. At the same time, though I can also see people getting into trouble doing that. I'm not trying to be negative — I can understand why people do it, I can understand the idea behind it. I love crowdfunding from a general perspective. I love the idea of getting the audience enthused and excited about what you're going to do. I think going forward crowdfunding is going to be a really important mechanism for all sorts of creative endeavors. But, it isn't all upside, is what I'm trying to say.

Q: You raised another interesting idea there about who can be considered ‘indie.’ I’ve definitely heard similar things from smaller studios about which devs can claim the ‘indie’ title. Can you unpack that a little more?

A: I guess that's in the eye of the beholder. What indie means to you is possibly different from what it means to me, or to a third person. There are gray areas when it comes to indie. It can be an attitude, but can also literally be whether you're owned by a multinational corporation or not. A game style could be indie, perhaps. I've got colleagues who talk about indie games as great ideas that are lacking on the delivery side of things. Indie developers might have a lot of ambition, but they can't build big environments and things like that. They have to use procedurally-generated landscapes or simplified graphics, which is great, because you’re using what you’ve got to your best advantage.

I guess they have the same argument in the music industry. What's an indie band? And when does a band stop being indie? There are huge arguments over genres of music as well. You know, what is metal? What's rock? What's country? It’s up to those specialists to tell me.

Q: It’s one of those never–ending debates.

A: And it’s a good debate. It’s one of those arguments that you can have with your friends, where you sit down and argue for hours about what indie is or isn’t. Everybody's right. And everybody's wrong. It's just a viewpoint.

Q: Let’s jump back to Rebellion as a studio. It seems like you have had your fingers in a lot of different pies, as far as business ventures are concerned. How did the company, and its staff, grow and adapt to those new endeavors over the last three decades?

A: Sometimes with difficulty. When we first started, we would have what we called our production meeting. Chris and I would sit down on a Monday morning and go, ‘right, what are we going to do? What are we going to try and achieve this week?’ We'd write things down and make lists.

Eventually we moved out of our office - out of the basement of our house - into an actual office. And we had what at the time seemed like a big round table that could probably sit around eight people. That was a big table for us at the time. We’d have the whole company sit around and talk about what we were going to do the next week.

Nowadays, we still have Monday production meetings, but there must be roughly 30 people in those meetings, which is itself a tiny fraction of the company. We’ll give summaries of what everyone is working on for the week. The idea is for people who are working on Project A to know what Project B is doing, and things like that.

Although the size has changed, we still do those meetings. The principle of having a weekly catch-up is really important.

You know, I was in the office recently, and somebody walked past, and it suddenly occurred to me that I didn't know whether that person was a burglar or whether they worked for me, because I've never met them in real life. I realized I didn’t even their name, which is awful. That's been made more difficult because of COVID, too, with people working from home a lot. That’s obviously not an ideal situation, but there is no way I can remember the names and the backgrounds of 550 full-time members of staff anymore.

At the end of the day, both Chris and I are games makers. We still get involved daily in making the games, and we still play the games we make. It's really important to us to be both business owners and business drivers, but we do this not because we want to run a business, but because we want to make games, publish books, make films and TV. That’s what motivates us: doing cool stuff.

I always try to tell new staff, if my door’s open, and I'm not on the phone, come and talk to me, if you've got anything you want to show me. That doesn't always happen, because they're far too nervous to talk to me, because they've read about me in the press, or they've seen interviews I've given or, they grew up being inspired by my work. They see me as some kind of semi-mythical figure in game design. Maybe I am, because I've been in it for a long time. But no, I'm not. I’m a guy that really likes making and playing computer games as well.

Q: Do you find it difficult to balance your celebrity status in the games industry with your desire to connect with the people working at Rebellion?

A: Yeah. You have to make time to humanize yourself as well. It’s a big company, and we're now well-known around the world. Lots of people want to talk to us, or pitch ideas. You can have meaningful conversations with people, but it can sometimes be a bit fannish. Something happened to me quite recently, when I was traveling, I was in line at airport security, and a security guard who recognized me from my history YouTube channel, Modern History TV, brought me to another line and let me skip to the front. It probably saved me an hour waiting in line for security. It was great, but I felt a bit guilty. Why should I jump the queue? Quite frankly, I'm happy to stand in line.

Q: The perks and opportunities are good, but you also want to be viewed as a person.

A: Yes, exactly right.

Q: Let’s talk a bit about Rebellion’s games. I think it’s fair to say that the Sniper Elite series has been your biggest and most successful title. What does Sniper Elite mean to the studio, and what other games were instrumental in your growth?

A: Sniper Elite has been a huge success. It’s a global franchise now, right up there with some of the biggest franchises. The games are played by countless millions of people when they’re released, so it always goes to number one best-selling, which is gratifying. We characterize Sniper Elite as a “thinking person's shooter.” It’s not so much a twitchy kind of game where the challenge is ‘can you shoot faster than the other person.’ It's more mission-focused, and the player has to plan their moves. I love it, because it requires a bit more thinking than some other games. It does require acting fast sometimes, but it's more about thinking and preparing. I think that helps the game reach a wider demographic.

Sniper Elite was really our first self funded, self-published game. Up to that point, we'd been doing work for hire for other people. We've been hugely successful with Mission Impossible games, Star Wars games, Simpsons games, James Bond games. But, ultimately, those games were somebody else's, including our breakout title Aliens vs. Predator. We effectively gave birth to the Aliens vs Predator franchise, which is gratifying, of course, but the title wasn’t owned by us, it was owned by Fox, and now Disney. I think that makes the alien queen a Disney princess.

Sniper Elite, though, was the first game that was wholly us. We were the only party involved in making in, funding it, and releasing it. That was a sea change, for the company, along with the rise of digital delivery.

Q: What sort of challenges did you face getting started as a studio, and how have those challenges developed as you’ve grown?

A: I think one of the most challenging things for any indie games developer is getting a game finished. Doesn't matter whether it's good or bad, it's just getting it finished.

Ultimately, no game is good unless it's finished. You could argue that there some really good early access games that never got finished, that were potentially good. But that slightly blurs the definition. I think anybody that ever finishes a game, or anything creative, deserves a pat on the back from everybody. Even if the project is rubbish, they've at least finished it.

The hardest thing is starting a creative project. The second-hardest thing is finishing it. I applaud anybody that's ever started a creative project, and I doubly applaud anybody that has finished a creative project, because that takes guts and determination. Lots of people can come up with ideas, but ideas are the easy part, actually putting the idea into practice is a difficult thing to do.

Q: What are some of your biggest takeaways from the last 30 years?

A: Be pessimistic about timelines. If you think you can do something in a month, you probably can't, and you probably should give yourself two months to do it. If you think a game is going to be finished in a year, it is probably going to be 18 months, or two years. Assume you can't be 100% efficient, and assume you need breaks as well. And assume you'll have some bad days and some good days in the creative process.

Don’t beat yourself up about it. Unless there are aliens or androids among us, we're all human. We all have flaws. You will have good days and bad days. Don't let the bad days get you down more than they need to, and enjoy the good days.

Q: What would you say has been Rebellion’s biggest win? What’s been your biggest loss?

A: Our biggest win is obviously starting the company in the first place - having the guts to start it with the naivety of youth, not having a clue really how it was going to work. We didn’t know how to fill in forms for the bank or how to do taxes, or anything like that. Sometimes you’ve just got to fling yourself into the task, and you've got to learn on the job.

I'm a huge believer in trying new things and learning by doing. Book learning only goes so far. If you wanted to learn to play tennis, you could read a lot of books on how to play the game. But at some stage, you've got to get the kit on, grab a tennis racket and hit that ball backwards and forwards. The theory is very good, but you've also got to do the practice. You will probably realize you're not very good at tennis to begin with. The best tennis star in the world was once really crap at tennis.

Another important point for us was the rise in self-publishing. That freed us up to be the masters of our own destiny. We didn't have to deal with gatekeepers. I don't mind working with third parties, I don't mind working with agents, as long as they add value. I want everybody I work with to contribute more than they cost. If three people are working together, they need to work better together than each of us apart.

That’s been one of the bad experiences for us, dealing with people backing down on deals that we've done, not paying on time. That's a real problem. When you're in startup mode, and somebody promises to pay you, and you assume they're honest, it’s sad when they don't pay you, and you have to chase them down. It’s hard enough to do our job, let alone now chase the money.

Q: Is that something you experienced a lot when starting out?

A: Yeah, I wouldn't say it was common, but it wasn't uncommon. Most people we worked with were great, but just a few in our history have been really troublesome. It’s horrible, because it takes up all your time. You want to be making games and doing cool stuff, and you've got to chase somebody up for a payment.

There were some companies, that are still around, that would make a game cheaper for themselves by structuring a deal in which they would pay developers late the whole time. They’d do this when the game development was coming to an end so that the indie studios would use up all of the money they had saved, and then they’d offer to buy them to finish the game.

Q: Do you find yourself now offering advice to devs looking to get into relationships with these big companies?

A: Somebody will come to me and ask me for advice on something, or ask if a person is good to work with. I might say, ‘yeah, they're really good. They're really straightforward. They paid us on time. They're good to work with.’ Or, I might say, ‘you know, they've got a bit of a mixed reputation. Maybe I'd choose somebody else before I go to them.’

Most people in the industry are straightforward and great. There's just a few in the past that have been quite terrible some of the time.

Q: I want to ask about the future of Rebellion. What sort of projects are on the horizon?

A: We already have expertise in shooters and adventure shooters and that kind of thing. So, you History, fantasy, science fiction, stuff like that. We haven't announced anything at the moment. I think that'll be more next year, but we've got multiple projects in process at the moment within the company.

We want to work on originals as well, we don't want to just work on the next Sniper Elite. It’s important to do sequels, but we also want a third of the work we do in-house to be original: trying new things, inventing new genres, trying to come up with new ways of entertaining people.

We will probably experiment a little bit in other business models as well. There's the subscription model that Sony and Microsoft are looking at, and there's this whole debate around in-game purchases and loot boxes. We're not going to do loot boxes, but that is to say that there are new business models being experimented with.

And then, we have film and TV as well as publishing. We want to create stories for people to explore. This can be in games, which are obviously the biggest part of our industry, but we actually physically have our own film studio. We really want to do more in that space as well, with some of our brands and characters and intellectual property.

Q: Where do you see yourself, and Rebellion, in another 30 years?

A: Oh, God, well, in 30 years, I'll be quite old. I probably won't be riding horses as much as I do, I will still ride them, and I'll still be involved in making games and doing creative stuff. There's a lot of really exciting technology that is starting to go into film and TV. A lot of it is games technology, like the Unreal Engine. That's a space I'm really keen on exploring, because there is definitely a developing synergy between games and films and TV. We've got to work out how best to use that. I don't even know what that means, but it just strikes me that there should be a big overlap there.

Ultimately, we started Rebellion because we wanted to make cool things. And I hope that, 30 years from now, I can say that we’ve been making cool things for 60 years.

[END]