Pentiment starts with an old book, the first line appearing in Latin, ‘In principio erat Verbum’. It happens to be the beginning of the book of John from the Bible and translates into, "In the beginning was the Word." It is a sneaky and creative way to begin the game, as Pentiment is all about words and the mighty influence they contain. The small, 13-person development team at Obsidian Entertainment designed the narrative adventure of Pentiment to put that power directly in the player's hands, for better or for worse. The result is a choose-your-own-adventure game that challenges players and their choices in ways that are sometimes maddeningly subtle. Still, it ultimately creates an enjoyable, but entirely too short, experience rarely found in this day and age.

The very first thing a player does when starting the game is to erase that line, as well as the rest of the first page in the book - another salient visual as the player begins to write the story of Andreas Maler, a budding artist in the fictional town of Tasling during the 16th century. A sudden crisis in the town pulls Andreas deeper into the lives of everyone living and working there, and he must take action to save the life of someone close to him. The story evolves into more than just that as it goes on, but giving any other information is dipping a toe into spoiler territory. The story within Pentiment isn’t something new, but the actions and reactions based on the choices the player makes can drastically change how Andreas is viewed in Tasling. Whomever players choose to interact with and the choices they make during those interactions can have lasting effects from the beginning to the very end. Some are very subtle without seeming to have any effect until much later, while others are grandiose and change much larger aspects of the game almost immediately. Religion, politics, and love all will play various roles in choice-making and work to give players a plethora of options for how to go about navigating a society from centuries ago.

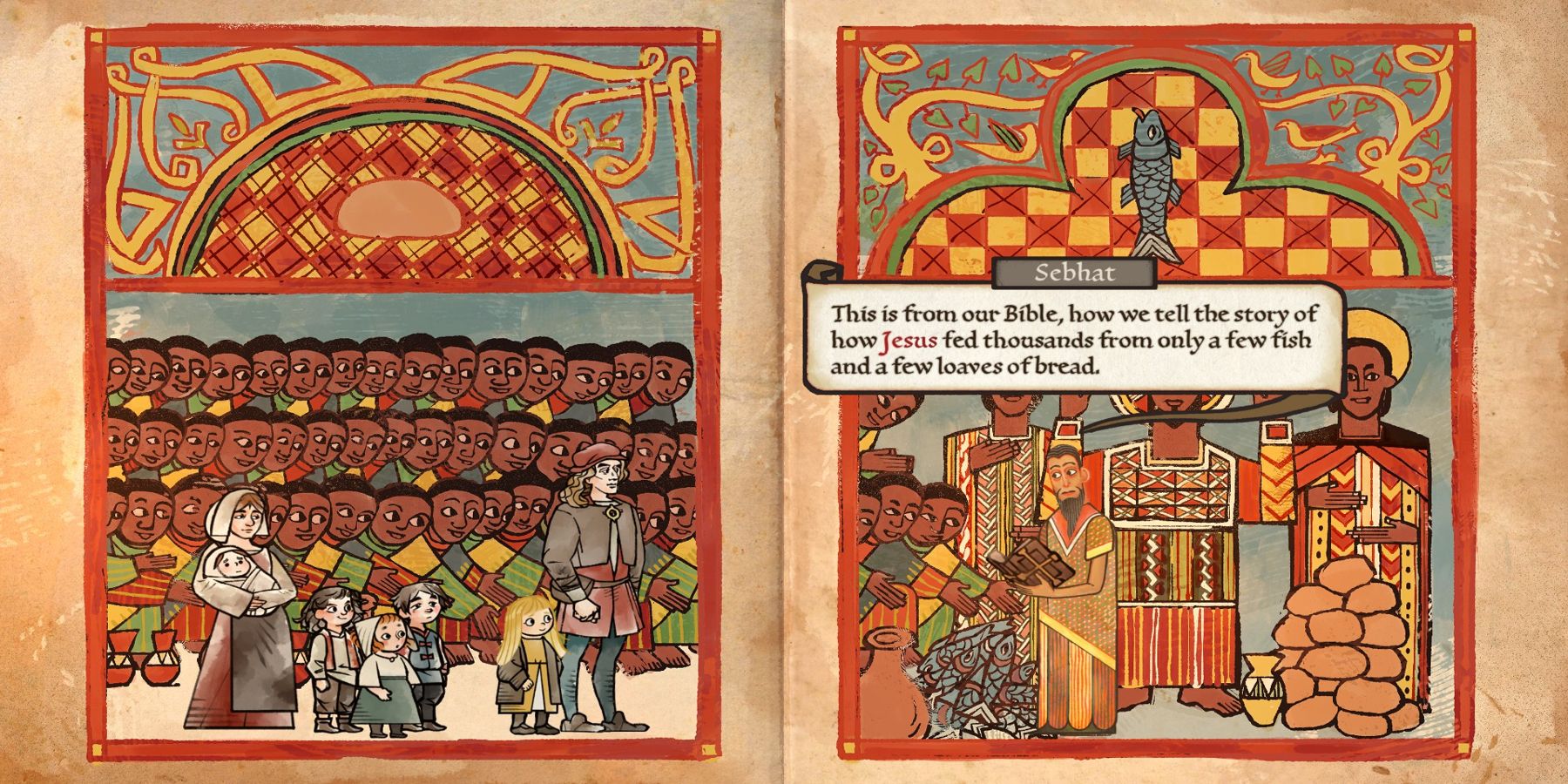

Pentiment is set in a time when religion permeates everyday life, and it doesn’t shy away from showing just how intrusive it was in the lives of both the clergy and the citizenry. From the protagonist, an artist that stands above the local peasantry while still renting a room from them, to the nuns and monks who relied on donations from patrons to survive but did not fear starving. The game seems to almost delight in showing the daily lives of both through dialogue and by splitting various activities into certain parts of the day. These include setting aside specific times for meals and when work was to be done that mirrors what society was like during that time.

Lovers of 16th-century art will adore Pentiment’s visual style, as the game is designed to look like a story found in an old tome. The gameplay itself copies the idea of being in a book very well, but it does take some liberties to ensure characters are more realistic and easily definable as compared to the olden days. This creates a wondrous sense of a storybook coming to life. It is visually striking and feels almost peculiar to watch a book become alive in this way. Character animations are mostly smooth, even with character models only being 2D and only ever able to face left or right. Walking and running animations look natural, and facial expressions are easily determinable and useful in figuring out a character's reaction to situations. Most character designs are good enough to differentiate characters, though some only use colors to separate certain women who wear almost the same thing.

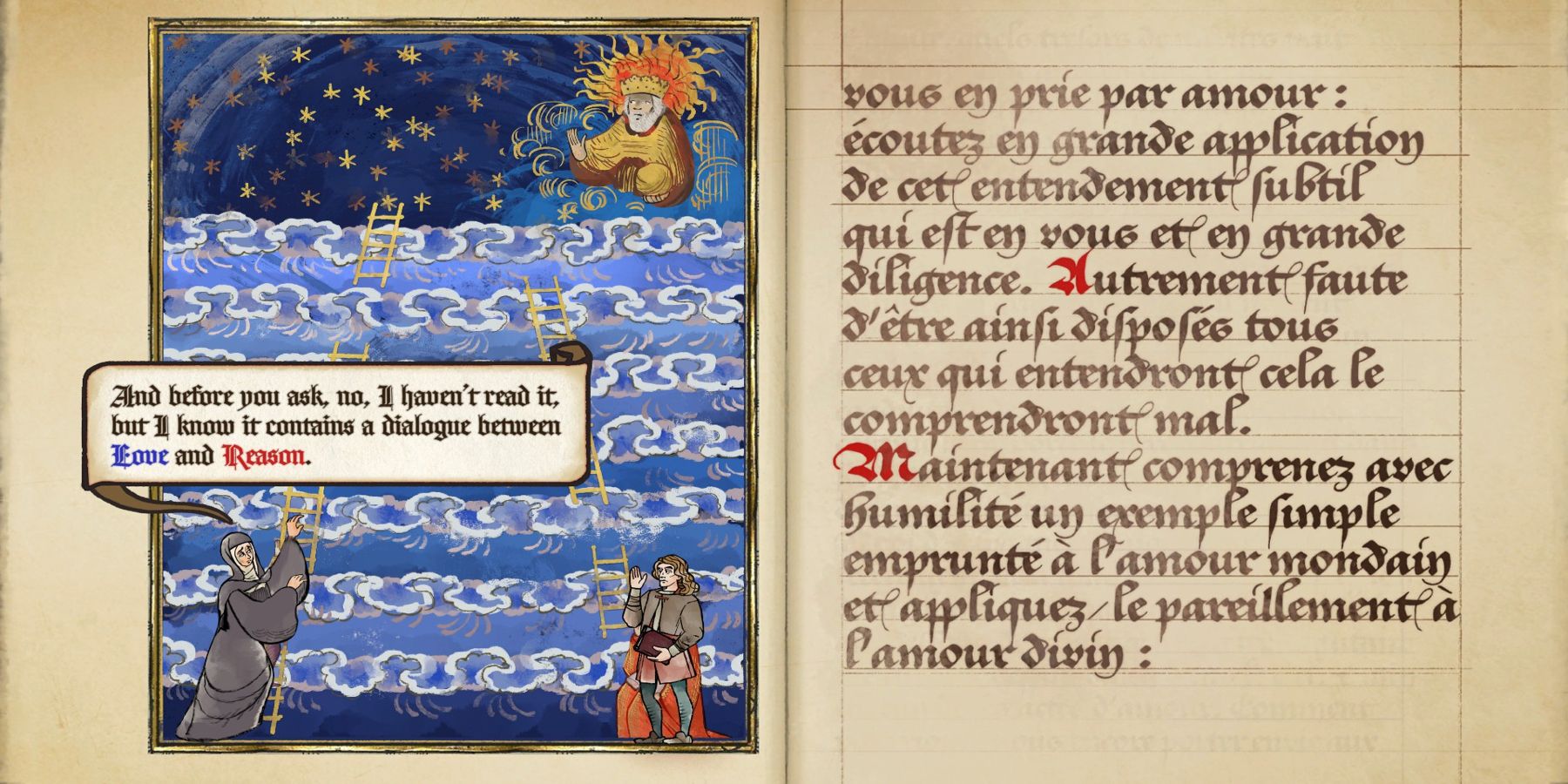

An intriguing aspect of the game that seems scarce in the current AAA landscape: Pentimenthas no voiced dialogue, aside from a monk that sings beautifully in the chapel. Instead, the game dialogue is written out in a few very interesting and diverse ways. Every character's spoken words are written as if someone was handwriting dialogue as it's being verbalized. It fits completely with the storybook aesthetic the game is portraying, as users hear the writing being scratched into the speech bubbles in real-time. The text styles even change depending on who is talking, as the monks and nuns are written in more formal Gothic-style typeset, while the peasantry is a more basic free-flowing cursive style. The developers were even able to show how holy words were written last and in red, as was the tradition due to changing ink colors. It also changes when talking to characters that use an early style printing press by setting the letters upside down and then flipping them like they were being printed.

The game uses this style to full effect by using things such as sudden ink splatter around words to indicate someone being agitated, distressed, or terrified. The developers also decided to add a red underline to certain named places and nouns to indicate there is more information to be gleaned about them. Clicking on one pulls the book away to show the picture on the page of the tome with indicators pointing to people or places named within, as well as definitions of words or phrases that have fallen out of use in current times. It was a well-thought-out addition, as most church practices of the 16th century are probably not known to the public anymore. Giving this information in the margins of the book the user is creating through their actions is a great way to not break immersion visually. There is a sometimes annoying aspect to this, as words can be misspelled when first written down, only for the game to erase the wrong word or letter and then fix it after the sentence is completed. For someone who reads quickly, it might trip up their thought process as they notice the misspelled word only for it to then be fixed when done reading. A minor qualm to be sure, but something that has the ability to become bothersome for fast readers.

Pentiment does a great job at not forcing players in certain directions when giving them options on where to explore or who to talk to next. Certain actions can’t be bypassed, but in between those the player is given free rein to explore the town and Abby as much as they want. The in-game map, which sits inside another book used as Andreas’ journal, gives indicators for some locations of interest during sections of the game where the player has options on who to talk to. Discovering different flowers, creatures, or clues is easy enough for those who like to explore, but after discovering all the areas it ends up feeling kind of small. Certain aspects of each area will change throughout the game, necessitating that users return to locations to search for new things to discover, but it doesn’t seem to expand the areas. For players expecting or used to giant expansive games, Pentiment might feel small and too confined. It does allow for a much more focused story though, so those more interested in the story than world building will feel very comfortable within its pages.

The game is full of positive aspects, but there are a few things that bring it down from being an exceptionally great title. The game feels longer on the first play-through but is decidedly shorter after learning character locations. A first play-through might take 15-20 hours or less, but the next few times through the game are decidedly more straightforward. It becomes stretched out and more annoying simply by the dialogue not being skippable. For those users who only have a limited time to game, Pentiment might scratch that itch, but players looking for something to occupy days at a time will likely finish the game and move on. Pentiment also doesn’t have manual saving as each action and decision is auto-saved immediately. For those who like to save before making big decisions, this can be frustrating, as it forces the player to repeat the entire game again to make different choices. Others will see it as a positive since it means they will have to stick with their decisions.

Obsidian and publisher Xbox Game Studios also decided to add options in the game that are either silly or helpful depending on a player's point of view. There is a big head mode, that can blow up characters' heads to comical proportions, as well as a voice assist option that allows players to use their own system to read out key texts. The former feels like a joke that designers didn’t want to remove, but the latter is a useful accessibility feature. The developers also include the option to change the stylized fonts to an easier-to-read script, though it does dilute some of the more stylized text into looking almost exactly the same.

The Italian word pentimento is defined as: an underlying image in a painting, one that only becomes visible when the top layer of paint turns transparent with age, showing evidence that it was revised by the artist. Pentiment smartly shares this definition through its replayability by placing a new story on top of the previous one, with the player painting a new history for Andreas and the town of Tasling each time. Some players may create chaos, others will try to keep the peace, but each will be able to tell the story of Pentiment in their own way. It is interactive choose-your-own-adventure story-telling at its best, and although it feels too short, hopefully, there will be more tales and tomes like this one from Obsidian in the future.

Pentiment releases November 15 for PC, Xbox One, and Xbox Series X|S. Game ZXC was provided a PC code for the purposes of this review.