Many players agree that while Skyrim’s main throughline is interesting because of the primary Shouts they learn, the game is at its best when players are instead exploring the continent and indulging in all its other content. Open-world games commonly boast a dense and immersive map with tons of satisfying interactions around each corner, but it must also be fulfilling and alluring. It may seem obvious to say that an open-world game is good if its open world is good, but too often these games are forgiving of mediocre narrative threads that behave as main quest campaigns.

Main campaigns serve a great purpose in a lot of open-world games, whether they ground them in a narrative or simply give players something to strive toward. But not every open-world game should need a critical path if it serves as an elementary tutorial, or if one is back-burnered in order to make the open-world engaging. This would not apply to all open-world games, but some open-world titles could benefit from omitting a narrative throughline and concentrating their efforts on wholly engrossing players in the open world.

Main Campaigns Can Pad Out an Open-World Experience

Players often have to balance their time between progressing enough of the main narrative before more of the map can open up for optional exploration. Locations can be inaccessible before a certain amount of progress is completed, for example, or locations can be accessible with the idle threat lingering of tougher enemies residing there.

Story beats can be padded out this way, where quest-related missions have players simply running between different areas instead of moving the narrative along promptly as it should. This padding has recently been produced by tasking players with finding and purging landmarks where more of the map can then be accessed, such as Assassin’s Creed’s viewpoints or Ghostwire: Tokyo’s Torii gates.

These kinds of quests are acceptable when players go about them on their own, but when included in a main campaign path it feels like a chore. In a narrative-driven open-world game, the story should be allowed to advance time in the game world and affect the open world accordingly. If players had not completed something they wanted to, then that would effectively be their mistake because there had been nothing stopping them from completing that goal earlier.

However, many open-world games give players the idea that its content will be there for them to rummage through at their leisure, whether they instantly complete everything that comes their way or decide to tackle it all once the story is finished and credits have rolled. Rather, some games lock players out from continuing with their adventure after credits have rolled, while some offer a New Game Plus option or simply send players back to a point in the narrative before progress had become irreversible.

Open-World Games Can Often Feel Ironically Restrictive

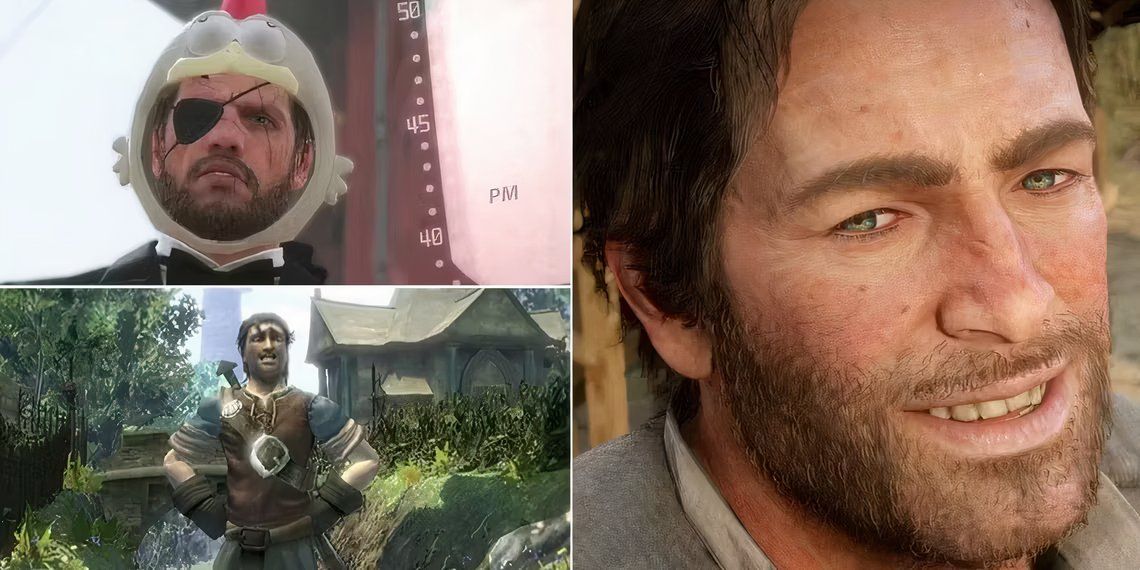

Further, open-world games that have linear narrative missions are completely paradoxical. The open-world portion may be fun and captivating with lots of NPC interaction, but then players enter hard-cut mission levels that leash them to rigid environmental boundaries. This is an antithetical experience that accentuates how favorable an open world can be in opposition to a main campaign.

The fantasy of an open sandbox with unlimited player freedom is proposed in the Red Dead Redemption franchise, The Elder Scrolls franchise, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, and The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. Some of these games have phenomenal narratives that punctuate the exploration players have at their fingertips, but it is also great for a game to unapologetically wish for players to freely explore without there needing to be a story to fall back on.

The question then is what an open-world game would look like if it had its campaign throughline completely omitted. For many games, this could mean that they would collapse in on themselves without that structure, but for many, it could likely be a fun experience with smaller narrative threads to follow instead.

Perhaps the biggest issue with a game like this would be how players would know to put it down, and the enormity of it could be much too overwhelming and daunting if the map was as big as most modern open-world RPGs—for example, Bethesda’s Starfield and Ubisoft’s open-world Star Wars game are intended to be massive undertakings.

Main Campaigns Are Often Good for a Structured Experience

Of course, having an open world be the main feature of a game and excluding a main narrative would be difficult to pull off and may not be as satisfying to players. Side content in open-world games often tends to become leftover missions that players will eventually get to after they complete the narrative, but that can be tedious if it is only the scraps of enemy encounters or myriad collectibles to clean up.

Many players need an end goal to strive toward in games—in most cases, hitting the credits. Credits inform the player that they have finished the game’s central content, and that any other adventures or interactions they choose to have are entirely optional, such as back-tracking to locations players have been to before now that they have unlocked a particular ability.

If an open-world game did not have a main throughline, it would be up to the player’s discretion when they decide to put it down for good, or once they have combed through every inch of the game and found every collectible. Some players decide to put a game down once they have finished hunting for each achievement it has to offer, but not every player would have that obligation or desire.

Moreover, not every player may want to explore an open world for all it is worth and simply enjoy running around for a while. It would take a particular kind of game to warrant having no narrative campaign, but there are certainly merits to this idea if a game is truly discovery-driven, like Minecraft. If the experience of a game’s open world is decidedly better than its narrative, then having a narrative that drags players through the open world can make it feel like a slog that they would not want to put themselves through again.

If players want to freely trek around mountainous gorges and deliver cargo in Death Stranding, that would be fantastic as its own experience without ties to an overarching narrative. There is no single solution or substitution to a main campaign in an open-world game, but perhaps the takeaway is that open-world games should be allowed to place focus on their open worlds rather than on the narrative backbones that they are often structured around.