Nisio Isin’s Monogatari series has made for one of Studio Shaft’s most acclaimed animated series ever, praised for its clever, snappy writing, and relentlessly eye-catching aesthetic. But one of the things that keep its story fresh across its multiple seasons, OVAs, and films, is its use of perspective and how supporting characters become true protagonists.

Bakemonogatari premiered in 2009 to much fanfare, and it remains one of the best-selling TV anime of the 2000s in Japan. It tells the story of Koyomi Araragi, a half-vampire who comes to the aid of several young women all afflicted with some form of paranormal apparition, usually linked to past trauma, and how he befriends them along the way.

The “Three Seasons” Of Monogatari

There have been 12 entries in the Monogatari anime, including the TV seasons, the OVAs, the spinoff Koyomimonogatari, and all three Kizumonogatari movies. There are even more novels because the anime tends to combine multiple novels into one season. With that said, the entire novel series has been grouped into “seasons” similar to a TV show.

Monogatari Series: First Season contains all of Bakemonogatari as well as Kizumonogatari, Nisemonogatari, and Nekomonogatari: Kuro. All of these stories are told from Araragi’s perspective. The audience becomes quite familiar with him, his tastes, his dislikes, his eccentricities, and the empathy he carries for each of the female characters that are at the center of the series.

We learn about these girls and the burdens they carry through Araragi, just as we experience his male gaze toward them as well, occasionally to the series' detriment. All of it effectively paints Monogatari as Araragi’s story of self-growth through his friendship with numerous characters that come and go between arcs. And yet, Monogatari Series: Second Season, does something very different.

Except for Kabukimonogatari and Onimonogatari, the majority of the stories are told from the perspective of different characters. And this is a running theme of this season in particular as afterward, Monogatari Series: Final Season is narrated primarily by Araragi, from Tsukimonogatari until the very end in Zoku Owarimonogatari. As such, Second Season feels distinct in its approach to telling its stories.

Can You See What I See?

Ever notice how few people are in the background of scenes in the First Season? Almost all the time, the only people that appear to exist are the main characters. It’s like a stage play with only a small cast; one can assume others exist, but they’re only spoken of or even heard, not necessarily seen in full view.

At the end of Bakemonogatari’s TV run, Araragi spends an entire scene in the back seat of a car driven by Senjougahara’s father. For much of the scene, the audience only hears the father’s voice, but never sees his face, until the end of the scene. And because there have been so few character appearances other than Araragi and his friends, it hits that much more effectively.

This is a fairly consistent trait across the entire series, no matter who is the lead. Monogatari’s atmosphere thrives on creating very liminal, dreamlike planes where the main characters are the sole focal point. But when the role of narrator is filled by someone other than Araragi, that choice begins to feel half stylistic, half diegetic.

Otorimonogatari follows Nadeko on her downward spiral toward becoming a god, and the antagonist of Koimonogatari at the end of the season. During the third episode of that arc, she’s confronted by a professor who asks her about the status of something she was working on, and she uncharacteristically snaps at him.

During this incredible scene where voice actress Kana Hanazawa is allowed to be really mean for a change, the student body, who appear as silhouettes in the halls, all react to her. It’s perhaps the largest crowd of characters in a single scene from Monogatari and despite the lack of detail, it says a lot about the way the world of the series is shown to audiences.

As a character, Nadeko’s burdens are far more tied to what others think of her and the way she presents herself, so it makes sense to acknowledge the people around her. Similarly, when characters like Kanbaru or Kaiki are the protagonists, there are more instances of named minor characters with full character designs or crowds in the background of certain scenes.

Suddenly, the aesthetic of Monogatari informs the diegesis, and the few instances where the viewer witnesses background characters inform the narrator’s relationship with people. Hanekawa and Araragi both carry emotional baggage be it the former’s troubled home life or the latter’s self-loathing. Their closed-off nature is reflected in how few people they truly see.

Realistically, there are probably tons of people in the background, but we don’t see them because stylistically they're unimportant and because narratively, the characters don’t register them. Outside the main cast, Araragi doesn’t have many friends, so to see the cast expand as it does is like watching Araragi’s world suddenly becoming more populated as he matures.

Fleshing Out The Cast

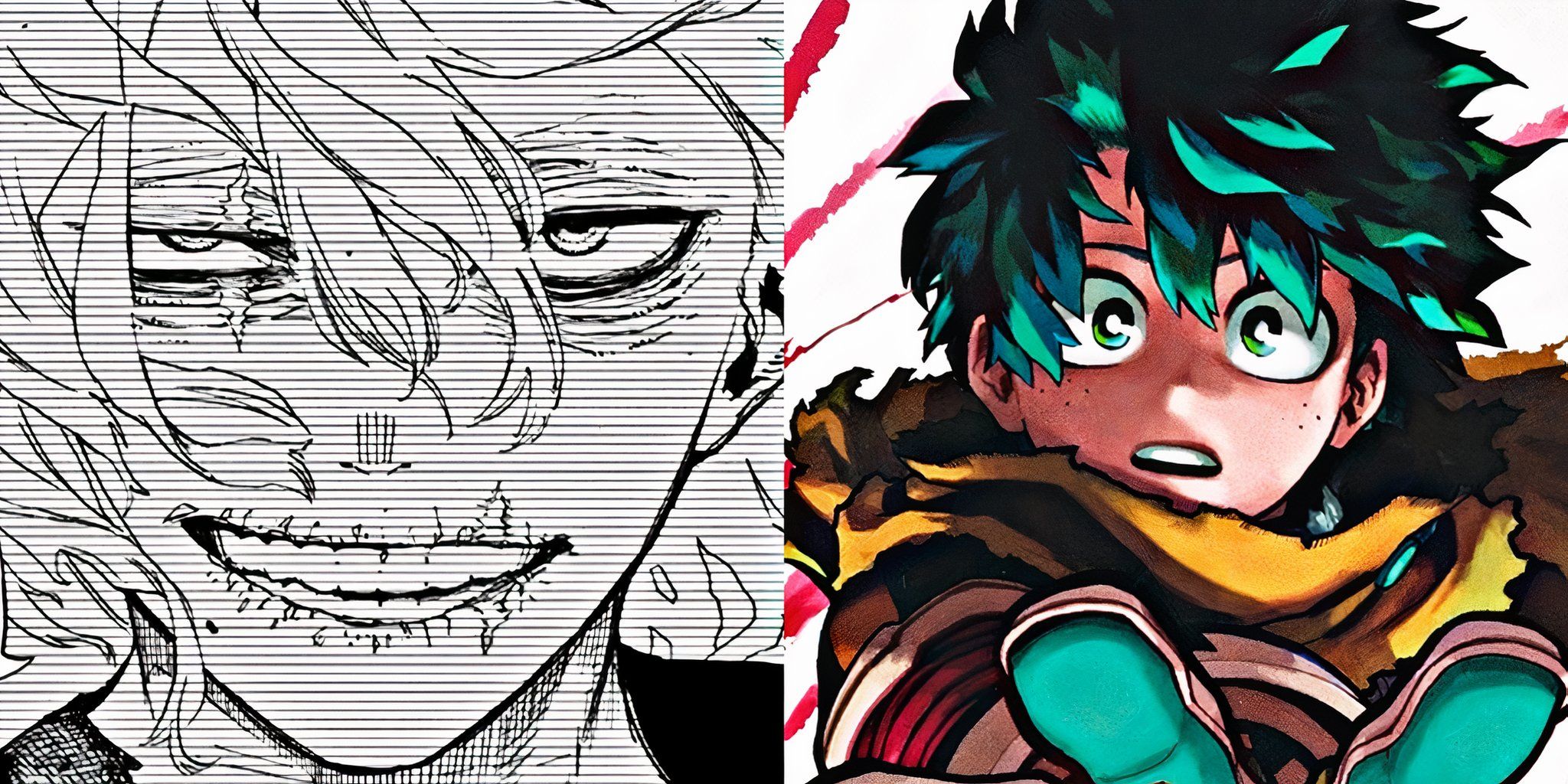

Monogatari Series: Second Season might be the best of the three seasons of the franchise, precisely because it changes perspective, enriching a cast that was already beloved. The aforementioned Otorimonogatari is exceptional not just for how it builds up the climactic arc, but because it fixes the underlying problems with Sengoku Nadeko.

There was never much to Nadeko besides her childish crush on Araragi and everyone generally thought that she was cute. And her sexualization combined with this lack of depth made her something of an uncomfortable character. As soon as the audience experiences her shyness and anxiety from her own perspective, it becomes so much more real.

The story attacks her very character and forces her to question who she is and who she wants to be, a conflict not resolved until the season’s end when Kaiki helps her. And Araragi doesn’t even get to swoop in and save the day like in Nekomongatari: Shiro, because the story was about how Nadeko needed to forget Araragi.

Hanamonogatari goes one step further, set after the events of the entire Monogatari story, once Araragi has graduated and is absent from the story. He does make an appearance but in a purely supportive role. It’s a phenomenal story about how neither time nor running away solves problems and how people confront and live with problems. And it’s hard to imagine the story being the same if Araragi was the lead.

The lesson of Monogatari Series: Second Season is that the franchise is not just Araragi’s story, but an eclectic collection of peoples’ stories. It’s a story of a city, where the paranormal is a vehicle for relatively small, relatable, mundane, and utterly human stories. It just so happens that Araragi is the central, most important figure, whom the story follows at the beginning and the end.