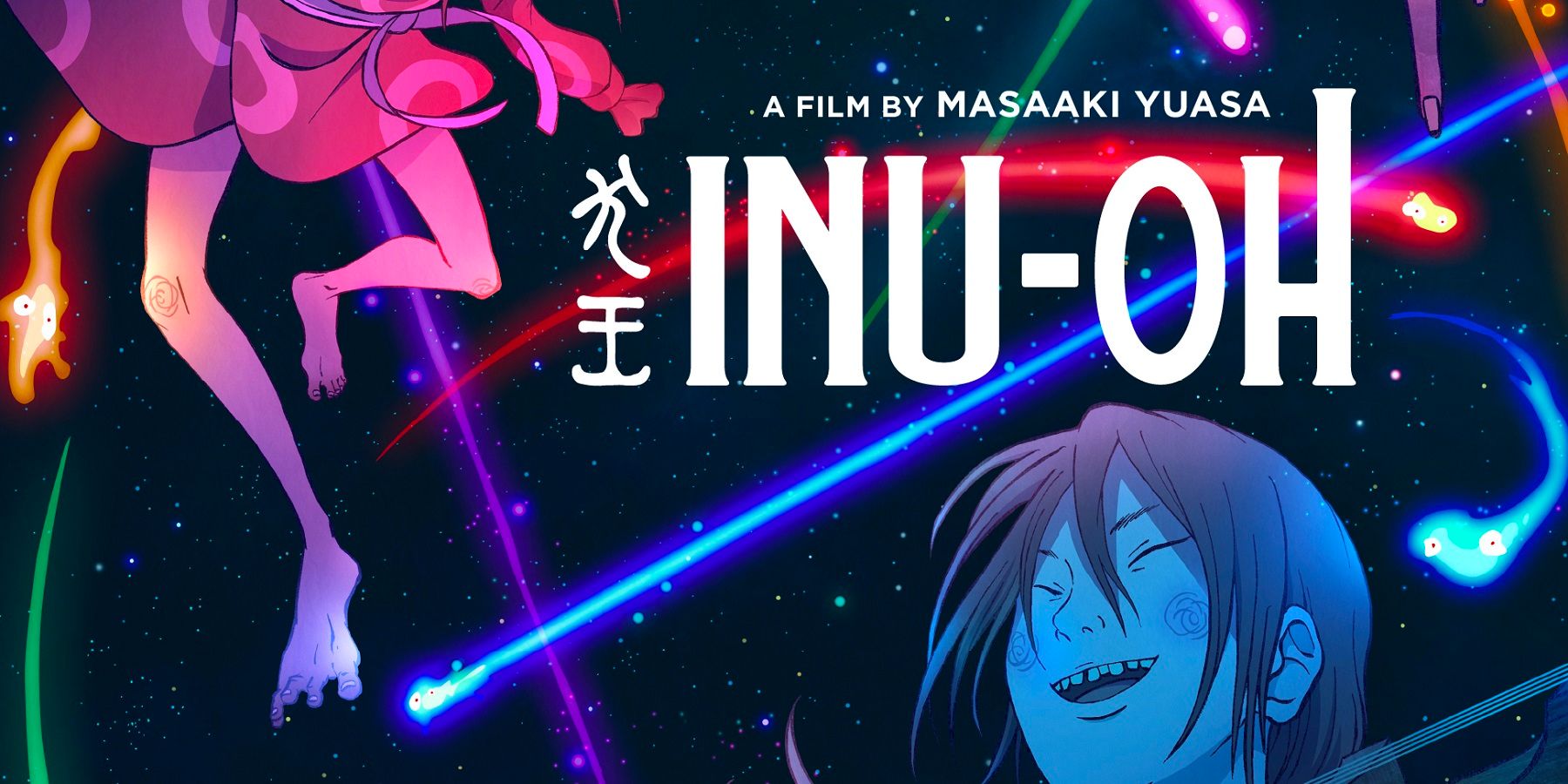

As the director of anime films ranging from the surrealist Mind Game and Night is Short, Walk on Girl, to the heartfelt stories of Lu Over the Wall and Ride Your Wave, to his showrunning for offbeat anime series like Ping Pong: The Animation and The Tatami Galaxy, there has never been—and perhaps never will be—another creator quite like Masaaki Yuasa. In many ways the director’s final film, Inu-Oh, serves as a rumination on the very act of artistic innovation. Weaving the story of two outcast musicians daring to introduce new styles and stories into the rigid traditions of Japanese biwa music, Science SARU co-founder Masaaki Yuasa’s swan song is at once an engrossing musical and a cerebral sendoff to one of anime’s most respected, idiosyncratic auteurs.

Set in feudal Japan, Inu-Oh is about a young blind biwa player, Tomona, who makes the acquaintance of an unnamed, grotesquely deformed performer hiding beneath a gourd-shaped mask. The two begin a unique partnership, with the performer, adopting the stage name “Inu-Oh,” beginning to integrate his own style performances into the biwa player’s set of new songs based around the legendary exploits of the ancient Heike clan.

When this shocking new performance style makes them the first ever rockstars, they form a rift with the old-guard of biwa and, perhaps, even the highest forces of the Shogunate. These uproars coincide with struggles over both Tomona and Inu-Oh’s identities as performers, some major performances deciding the fate of Japanese music are played out on the chords of a rock-opera epic.

The terms like “rock-opera,” “rockstar,” and “musical” swirl around the marketing and reviews for Inu-Oh, deservedly so. That all on the table, it must be stated: this is no Love Live!. The musical structure of the film takes its cues from Noh theater and traditional music much more than what springs to mind when one imagines a Hollywood musical or a Japanese idol concert. This results in a musicality that is less about specific songs or tracks appearing in a hypothetical hitlist, and more reflective a steady strumming of Japanese strings to capture and revitalize the performances of a bygone era.

These performance scenes are visually dedicated to the craft of theatricality and, in their lyrics, very explicitly tied to orally reciting the legends of the Heike over narrating anything felt by the performers or needed for the overarching plot of the film itself. While the structuring of the music’s presentation is decidedly inspired by traditional influences, certain aspects of modern rock music are, entertainingly, on full display.

The ingenuity with which the performances are staged becomes a surprising source of the film’s visual treatment; seeing the improbable use of feudal-era technology to create special effects akin to a modern rock concert is oddly satisfying. The essential takeaway is that this anime rock musical may, subversively, end up less familiar to K-On! musical stans and more at home dancing in the twofold shadows of traditional Noh theater and Freddy Mercury.

In many ways, the titular outcast of Inu-Oh is reminiscent of the also titular singing mermaid of Yuasa’s 2017 feature Lu Over the Wall. The music that these characters provide is always entertaining and upbeat, but it at times can run the risk of feeling more like these characters exist to perkily provide their music rather than fully illustrate themselves as multidimensional. This protagonist’s deformed appearance is repeatedly remarked as alienating and grotesque for plot-centric reasons, but Inu-Oh hardly shows any anxiety over any of it when compared to the existential identity issues of Tomona as his changes of identity impact his ancestral relationships. (Tomona and his identity—specifically his name—are a big sideplot of the film that needs not spoiling here).

The dynamic between the two musicians is established rather quickly, and there isn’t as much of an emphasis on their personal training and mastery of music that one might expect. Like so many international animated films, its rating (in this case PG-13) is less a statement on its seeming intended audience and more an assessment of what it does and doesn’t show. The film is definitely dark and grotesque for kids, most notably in a moment of almost comedically over-the-top gore (which is no stranger to Yuasa's corpus)—you’ll know it when you see it—near the end of the film.

It is less apt to call Inu-Oh Masaaki Yuasa’s final singular masterwork and more fitting to see it as the last patch sewn into the holistic quilt of his acclaimed style. The film is best appreciated when those familiar with Science SARU will notice the subtleties, when a scene where the voice directing for Inu-Oh and Tomona shares energy with the Protatonist and Ozu of The Tatami Galaxy, or speculating on the directorial intent behind a certain scene feeling more stylistically similar to Ping Pong: The Animation or Lu Over the Wall.

Likewise, Inu-Oh very consciously plays with synergy between the anime series, The Heike Story, that was released earlier this year by Science SARU. While Yuasa did not himself direct The Heike Story, the interplay between the series and the film is recollective of that between The Tatami Galaxy and Night is Short, Walk on Girl. Yuasa has created his entirely own audiovisual grammar for anime, and the film’s concluding contemplation of the artistic influence of its protagonists into the present day is, definitively, about its director and studios ongoing relationship to the larger anime medium. It can function both as a given treat for devotees of Science SARU and a nice introduction to the style and larger universe of the studio for newcomers. Sometimes the quirks and puzzles are their own reward, and sometimes the joy is just losing yourself in the beat.

Now playing in North American theaters. For information, see GKIDS.

Inu-Oh