For a small cabal of die-hard book fans, the Harry Potter movies were an unmitigated travesty. From illogical plot changes (how will Harry find the diadem if Ginny hides the Prince’s book?) to minor aesthetic alterations (Barty Crouch Junior’s hair color is supposed to be “sandy”), the movies seemed to disregard the text entirely. Changes ranged from unnecessary to reasonable, but the question they provoked was legitimate: Why make changes at all?

The books of the Harry Potter series were the most-read in history; the movies would have been successful even if they were only seen by book fans. But they were not only seen by book fans, and the movies cemented Harry Potter’s status as an enduring, endlessly bankable franchise. Therein lies a fable for all adaptations—viewers cannot expect screen adaptations to maintain fidelity to source material…nor should they.

Adaptations are popular for the same reason that spinoffs exist: fans want more of what they already love. As a narrative form, adaptation will always be attractive to storytellers—a chance to bring their own vision to the stories that inspired their craft. For fans, adaptations provide a ‘more real’ mode of experiencing those stories, with each iteration rendering more detail into the gaps of imagination. In the time of the proverbial Ancients, writers adapted the archetypes of myth into plays. In its century of existence, Hollywood has produced countless movies based on books. Now, the video game adaptation is ascendant, with bingeable storylines constructed around the quests and gear of games. With the success of The Witcher (Netflix), Arcane (also Netflix), and Halo (Paramount+), streaming studios are rushing to turn gamers into viewers—and subscribers.

Yet gamers, it would seem, are not so easily satisfied as the legions of Harry Potter fans who paid theater prices year after year to watch Warner Bros. desecrate their beloved series. The difference is not necessarily one of source material—after all, The Witcher has plenty of book readers who have joined their voices with gamers to decry Netflix’s version of the franchise. The Halo series, too, has been denounced for including that most basic of narrative structures, the romance plot. The titles, sources, and objections may vary, but the message is the same: ‘Leave it alone.’ Fans would prefer that studios produce the material as-is, without major alterations to stories or characters.

Studios are not going to listen. Even if they were adapting the most ubiquitous franchise in human history, studios still would not listen. Netflix has proven time and again that there is no level of saturation that will satisfy its investors, a model that other streaming services are likely to co-opt, in hopes of emulating Netflix’s success. Moreover, creators will not be satisfied with reproducing their predecessors’ creative vision: writers and directors did not attain the status that allows them to produce big-budget adaptations by creating art devoid of their own authorship. Finally, practical considerations often necessitate alteration: budgets constrain to what degree fantasy premises can be realized, running times restrict the inclusion of expansive material, etc. Creators must always balance the practical with the artistic, and adding a need for fidelity only complicates their task; they cannot be beholden to every detail of source material.

But studios also should not listen. Often, books contain narrative weak points or objectionable material that will not hold up onscreen—by removing these issues, adaptations can actually improve upon the original work. Netflix’s The Witcher has done exactly that, and it has thereby managed to expand the franchise’s fanbase, pointing new fans towards the books and games. But even without these issues, adapting a video game entails crafting an original story. Video games are not an inherently narrative medium (per se—obviously there are exceptions, as What Remains of Edith Finch or To The Moon). While many games have a narrative, telling a user-directed story is not the same as constructing a holistic story, one not subject to audience choices. Instead of being manipulated by players, movie and television plots are driven by characters and themes—elements which are not necessarily united to action in video games.

Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogies together provide a perfect case study in the considerations of adaptation. One trilogy set the standard for crowd-pleasing, worthy adaptation; the other also set a standard—for unnecessary narrative bloat. The Lord of the Rings movies are by no means completely faithful to the books: besides the many plot points that were left out, whole characters and arcs were changed to fit the screen narrative. Faramir, for instance, was rewritten entirely, from his story arc to his fundamental characterization (not to mention his romance plot with Eowyn, which is reduced to a footnote). Yet Faramir’s narrative makes sense within the space of the movies—particularly The Two Towers, in which his temptation lends tension to the Frodo/Sam subplot, enlivening their otherwise-monotonous trudge toward Mount Doom.

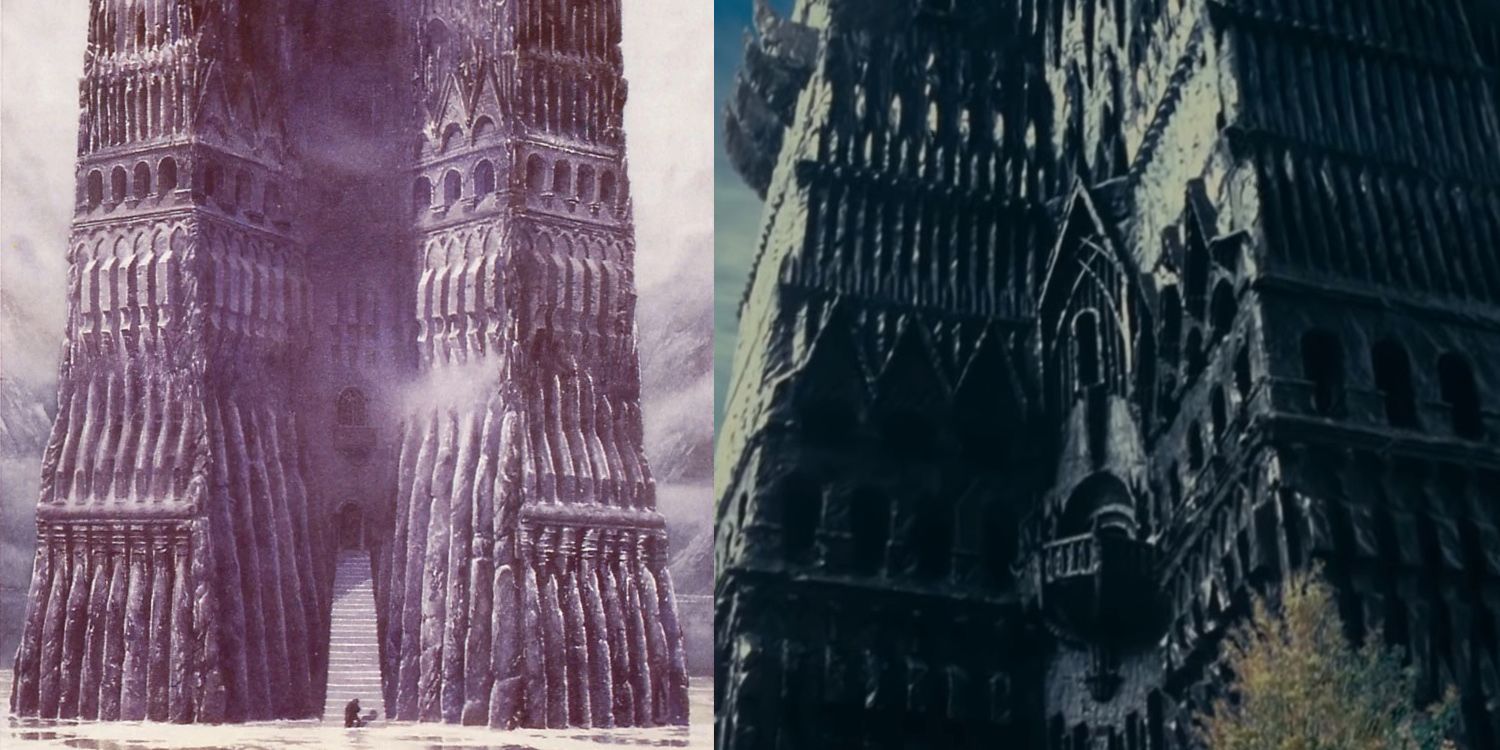

Most importantly, The Lord of the Rings succeeds in rendering the aesthetic of Middle Earth (Orthanc looks exactly like the cover art for The Two Towers) and in capturing the spirit of the books faithfully. The themes and mood are still the same, even if individual details are different. Unfortunately, The Hobbit failed to replicate that fidelity, much to its detriment. The Hobbit is a short book, fast-paced and rollicking from adventure to adventure—a traditional epic, told in an eminently engaging style. Adapting such a page-turner into three movies was Jackson’s first mistake: there is simply not enough material in the book to fill six-plus hours of screen time. Fans were put off by gratuitous side plots (including, again, a romance plot) and meandering lore—and rightly so, as the changes Jackson made neither resemble the book nor enhance the movies.

In evaluating this balance—between faithful essence and practical alteration—it is useful to return, again, to Harry Potter, to the strongest adaptation in the series. Like the other installments, Prisoner of Azkaban is rife with changes: How is Harry practicing magic outside of school? Who are the Marauders? Since when does Hogwarts have a choir? Many of these changes are unnecessary and damaging to the plot, but the movie stands out for constructing a world that feels both real and magical—more real and more magical than the world of the other movies (in some ways, even, than that of the books). It makes sense that Hogwarts has a choir; it’s a boarding school, after all, and showing students singing at the start of the Halloween Feast adds mood and depth to the scene. Alfonso Cuarón is an exceptional director, and he surpassed his peers by infusing the existing material with his own imagination.

Regardless of their successes or failures as adaptations, all three of these franchises brought in new, movies-only fans. The inescapable reality is that fans nowadays will usually turn out for the material they love (at least once), regardless of how it is presented. The job of an adaptation is to expand that base, and doing so requires creators to make changes, usually by adding elements that were not part of the ‘original’ media—that will attract audiences who did not find the source material attractive in the first place. Halo is an incredibly popular, long-running game; it is reasonable to assume that most everyone who would want to play it is aware that it exists. By making Master Chief accessible, Paramount+ catered to audiences who were uninterested in the game but interested in character-driven science fiction. Similarly, by empowering the female characters of The Witcher, Netflix expanded the show’s pool of female viewers.

That expansion matters, especially in the cutthroat climate of streaming, because existing fanbases are not always broad enough to support big-budget series. It is time for fans to accept that studios do not need their approval to create successful adaptations—but slavishly seeking their approval limits the potential for success. Rather than begging studios to leave source material alone, it is time for the fans themselves to adapt.