Given its status as a medium intrinsically bound to its creation in Japan, the localization of anime has been a focal point in its fandom for decades. Subtitles over Japanese-language audio are typically seen by many audiences as the default and most authentic means of viewing the original creators’ intent, and an increased openness to subtitled audio seems correlated to the increasing popularity of anime in recent years. However, dubs have remained an accessible and entertaining option as well, introducing countless fans to anime through outlets like [adult swim]’s Toonami, Likewise, the lauded English-language dubs of some anime like Cowboy Bebop and Baccano! are lauded by many as the definitive versions of their series.

Subs vs dubs is an ever-relevant issue for anime; it juggles the artistic aims of creators with audience preferences and the linguistic issues inherent to translation. Many North American dubbing companies, especially those aimed at younger audiences like DiC Entertainment in the 1990s and 4Kids in the 2000s, have faced more than a little banter among older fans for their sometimes-simplistic treatment of translations, especially in regard to elements of Japanese culture. While these historical examples certainly highlight the matrix of challenges involved in localization, such issues have been relevant to the anime industry since its earliest exports to international markets. Surprisingly, a now-obscure distribution company from the 80s and 90s served as the forerunner to many of the later discourses that impact the anime industry to this day.

Streamline Pictures

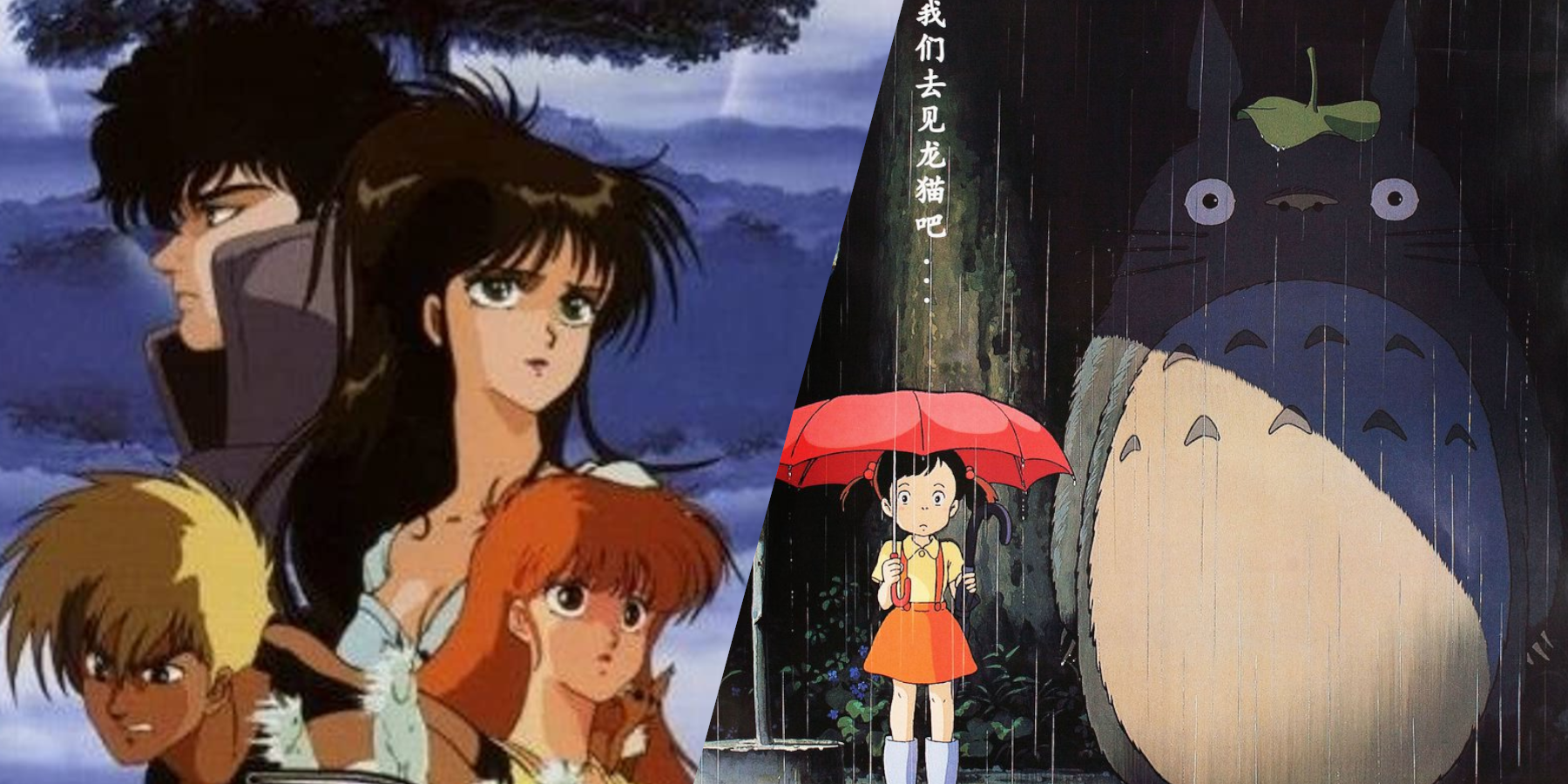

Founded in 1988 by animation and radio veterans Carl Macek, Fred Patten and Jerry Beck, Streamline Pictures was one of the first distribution companies that attempted to bring the then-niche medium of anime to a wider American audience. Devoted entirely to the distribution of anime (with the exception of a few different non-Japanese vintage animations), Streamline Pictures was the first international distributor of many iconic anime productions, including Hayao Miyazaki’s directorial debut The Castle of Cagliostro, many of the early studio Ghibli films, and Katsuhiro Otomo’s cyberpunk epic Akira.

Treading fairly new territory for localization (while the anime industry on the other side of the Pacific was itself charting new waters with the 1980s OVA system and many ambitious projects), Streamline Pictures’ early popularization of anime is a double-edged sword with its legacy as the first example of controversy in anime localization. Because there were so few examples of Japanese animation in American consciousness without any easy way of tracing them back to their original production, Streamline gained a reputation for playing fast and loose with a lot of their editing and dubbing. As Fred Patten recounted years later in a blog: “Carl insisted that all of Streamline’s videos would be dubbed, not subtitled, because the general public he wished to attract (he ignored the anime fans) would care not read subtitles for an animated feature. Sales – compared with the sales of other companies’ subtitled anime videos – proved that he was right.”

Anime Localization: Robotech vs Macross

The wild-west ethos of this early localization is best illustrated in the fact that one of Streamline’s most well-known series, Robotech, was in fact not its own show but an assembly from Carl Macek, written together from the clips of three different, unrelated anime. Taken from clips of the first Macross anime as well as Super Dimension Cavalry Cross and Genesis Climber MOSPEADA, Robotech used each of the different series' animation to form arcs and weave together a singular story through dialogue. Despite an exceedingly unorthodox production that would never fly in the modern industry, Macek’s Robotech was in fact quite successful, spanning 85 episodes in total and enjoying success on both its 1985 American release as well as a second-wind home release after Streamline’s founding in 1992 and a final hurrah during the early days of Cartoon Network’s Toonami in 1998. In fact, back then Toonami was arguably more associated with Hanna-Barbera action cartoons than with anime. Robotech, along with early dubs of Dragon Ball Z and DiC’s now-polarizing Sailor Moon dub helped to guide the block to a more direct focus on anime that has defined the block ever since.

Because Robotech borrowed so freely from its various source series for the re-assembled written dubs, Streamline’s approach became a prescient catalyst for discourse on dubbing, localization, and authenticity. This was especially true for fans of the Macross series, which later became its own popular franchise separately from its influence as one of the three series used to make Robotech. To Streamline’s credit, its home releases also included the occasional subtitle job, found in editions of Akira as well as a tape of original subtitled Macross episodes beside their dubbed, liberties-taken Robotech counterparts. Despite the divergence of the Macross franchise in the American consciousness, Robotech has remained its own popular franchise, continuing to release media with Macek's involvement as recently as 2013.

While the now-forgotten issues raised by Streamline sit by the wayside in modern anime discourse (nay, even to the wayside of more modern dubbing criticisms), the distributors’ work parallels many latter discussions about localization. The practice of re-editing footage to fit audience and company demands on Robotech was a forerunner of the discussions regarding the 2000 release of Digimon: The Movie as assembled from different materials in the Japanese series. Questions about localization to reach the broadest possible audience set the stage for latter discussion on the dubbing jobs by DiC and 4Kids. With the plethora of streaming options available online and the versatility of audio options on physical media, fans are much more in control of how they choose to watch their content. However, looking back on the history of anime localization, one can’t help but admire how far things have come, and how these discussions (or, in terms of subs vs dubs, debates) will likely continue for a long time to come.